About Politics of Knowledge (PoK)

Anke Haarmann

Out of focus! The problem is the blur! Fuzziness was once regarded as a promise, the pledge of a non-hegemonic pursuit of truth. The use of vague terminology serves to illustrate that the transitions in question can be fluid and that definitive definitions are not required. The acknowledgement of truth thus entails the understanding that it is not a standalone entity, but rather a complex and interrelated phenomenon. Nevertheless, from the history of thought, this objectivity was perceived as an imperative and an inescapable aspect of cognitive processes. However, it was constructed on a foundation of domination. It is therefore pertinent to inquire as to which parties determine the parameters of knowledge production and which discourses are employed by those who are held in esteem as authoritative sources.

The history of thought gave rise to a space of domination in which the positions of speakers, the legitimacy of vocabularies and the methods of acquiring knowledge were determined in advance. It is evident that these determinations are not the result of arbitrary or capricious actions, but rather, they emerge from the very tradition of thought itself. However, it is crucial to recognize that tradition is not an objective entity; rather, it is an accumulation of confirmations. The historical framework, particularly the Western historical narrative, has shaped the formation of these exclusions through the establishment of rigid boundaries, as evidenced by the definitions, determinations, and stipulations that have been put in place to exclude alternative forms of thinking, seeing, and recognizing. In his inaugural lecture at the Collège de France in 1970, Michel Foucault claimed, "that in every society the production of discourse is at once controlled, selected, organised and channelled - by certain procedures whose task it is to tame the forces and the dangers of discourse, to banish its unpredictable eventfulness, to circumvent its heavy and threatening materiality."

The introduction of blurriness as a concept has been a means of challenging the dominance of sharpness as a form of knowledge. This shift in perspective may not be entirely liberating, but it does indicate a need to embrace the ambiguity of not knowing and of other forms of knowledge. This diagnosis is still relevant and the research programme that Foucault began has not ended - only perhaps shifted, expanded, radicalised. It has also been enriched by the insights of Pierre Bourdieu, who in "Homo academicus" speaks of academia as a "social field" and draws attention to the respective "contexts of production and use" in which the sciences and humanities and their results are situated.

What is still decisive is that with the concept of "discourse", or that of the "field", truth and power, or knowledge and politics are to be thought together and analysed in their entanglement. And not only that. It is not only about seeing through, deciphering, and exposing the inner regulations of discourses or knowledge productions, because selection, control and thus exclusion mechanisms go hand in hand with the regulations. Knowledge production excludes other (perhaps not usable) knowledge. It is also about drawing conclusions from it: another kind of knowledge is necessary. But what does this look like - this other knowledge? How is it produced, what objects of knowledge does it have and who determines why this (other) knowledge may be considered true?

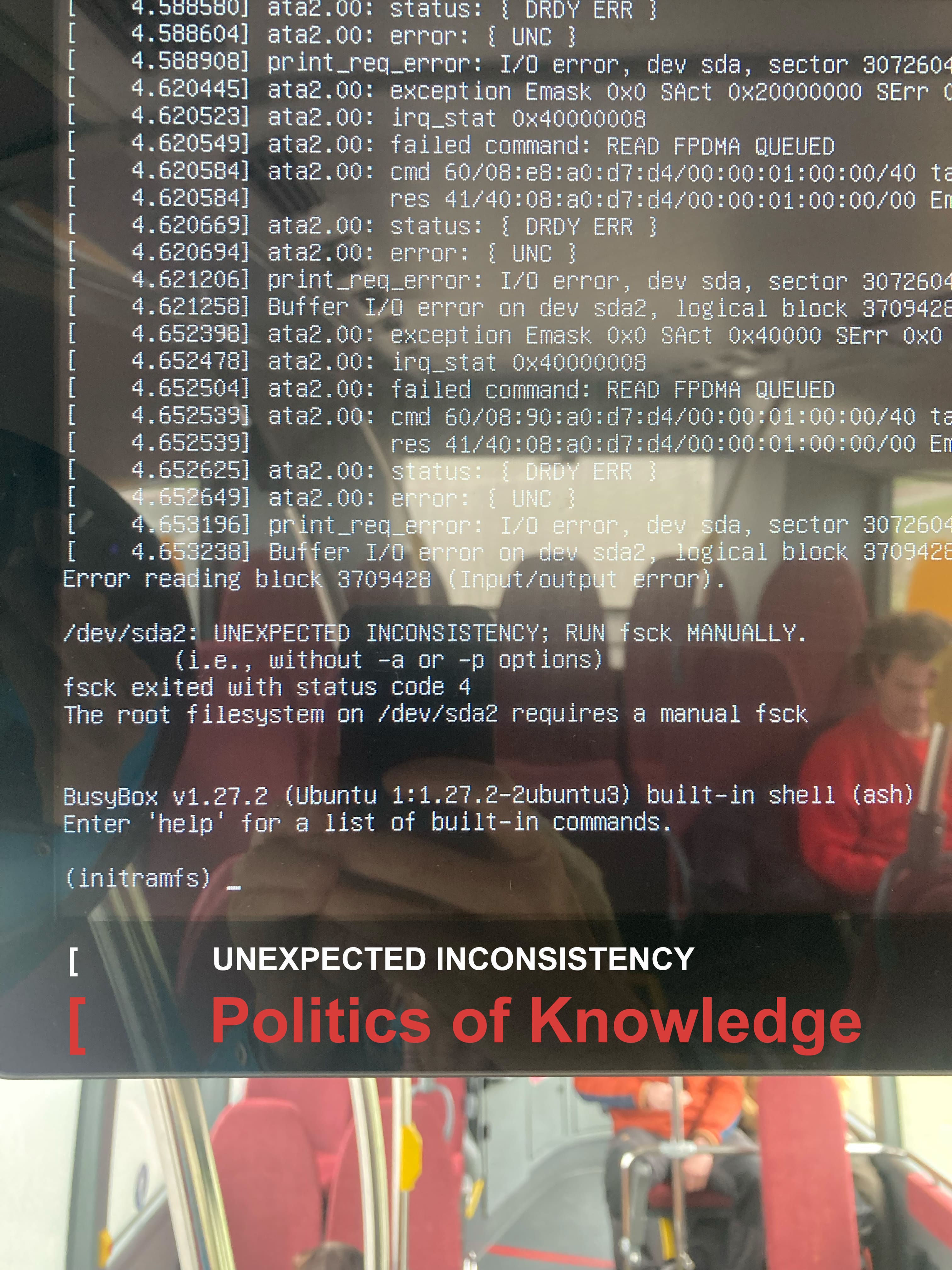

These are questions pertaining to the politics of knowledge, and they remain pertinent. This question of a politics of knowledge is posed in order to examine the relationship between truth and power, politics and knowledge, and exclusion and inclusion. It is asserted that alternative access to knowledge can be achieved through the utilisation of disparate practices and materials, which may or may not adhere to the tenets of scientific methodology. However, the question of access to knowledge (and the methods used to obtain it) is not the only aspect that differs between these forms of knowledge production. The topics and contents are also sometimes distinct. Matters that are deemed irrelevant, marginal, insignificant, or subjective are given attention and investigated. This approach seems promising, alternative, and inclusive. Nevertheless, it remains unclear how this alternative knowledge justifies itself, not only against traditional forms of knowledge, but also against "alternative truths" or "fake news." The question of a politics of knowledge is being posed in light of the fact that questioning knowledge has become problematic. An unexpected inconsistency has emerged. The inconsistency is that the questioning of hegemonic knowledge discourses has itself become a problem that strikes back hegemonically, like a boomerang. The problem is that truth cannot be based on anything, but then everything can be claimed as truth.

Motion blur. We traverse the countryside. The terrain is characterised by a beige hue. The image is blurred in accordance with the movement of the camera, thereby creating a picturesque effect. The picturesque quality of this blurriness offers a promise of hope and joy. This suggests that blurriness can be perceived as aesthetically pleasing. In light of this promise, we embark on a journey to the countryside and skip cheerfully through the landscape. We have transitioned from an academic perspective to a different conceptual space, which suggests that we will generate alternative perspectives to address the absence of definitive justification as a promise and as a challenge along this path (the journey to the countryside).

Our academic thinking was already distinct from the prevailing Western traditions of knowledge. Our academic thinking originated from an academy: an academy of fine arts. Such thinking was already informed by the aesthetic and shaped by the methods of artistic inquiry and comprehension. However, art as a form of knowledge or artistic research also confronts the dilemma that it promises a distinct understanding that differs from dominant knowledge discourses, yet it does not seek to be equated with alternative truths. It aspires to be distinctive yet not arbitrary. It aims to enlighten and foster new perspectives, yet it does not intend to impose blind ideological conformity. It endeavours to embrace mystical thinking, yet it does not intend to establish a new policy of discrimination based on it.

The field of artistic research finds itself situated within a historical context that encompasses both of the following: the coexistence of marginality and control, as well as exclusion from the realms of science and nascent internal selection processes, representing a significant challenge. The field is on the verge of becoming a "normal science," as postulated by Thomas Kuhn. It is simultaneously characterized by elements of both regulation and transgression. It permeates the very institutions it seeks to influence, while simultaneously forming alliances with them. How then, should we, as the primary stakeholders in artistic research, navigate this complex landscape? How should we conceptualize and operationalize this inherent ambivalence?

The research group "Politics of Knowledge" addressed the questions pertaining to the acquisition of knowledge in novel contexts. In the course of this process, it was necessary to subject the very concept of "artistic" to rigorous examination, particularly in terms of how it is researched and questioned. The concept of "other knowledge" is open to question, as is the question of who determines its relevance. The notion of "new contexts" is also worthy of examination, given that we are engaged in research within an institution that is both unusual (artistic) and ordinary (state-related). Furthermore, the question of the "others" with whom we cooperate is a significant one, given that it raises the issue of who gets access to the research and knowledge on the basis of what criteria.

A problematic situation arises when everyone claims everything, and no justification can ultimately contradict this. Conversely, a promising situation emerges when more than just a select few can make truthful claims and alternative contexts of justification assert themselves. In the context of land, headwinds at the edge of the sea or encounters with non-humans provoke us to engage differently or to make contact.

Politics of Knowledge (2022–24), Lectorate Art Theory & Practice at the Royal Academy of Arts.