Zuzanna Zgierska

In ancient Sumer, trade technology froze biological stocks into codified representations: resources defined by clay tokens separated from unaccounted natural noise. The muddy embodiments of debts allowed portions of matter to be divided, disposed, and described.[1] An invisible hand cast deadly varnish on a landscape in flux; borders replaced osmoses, and networks fell apart. Abstracted from nature, the financial system established a dualist hierarchy between humans, “(…) the active subjects, who give form and meaning, [and] the passive material or object, which is formless and senseless.”[2] Today, cash flows out of geological chaos prompted by the capitalist poetics of ‘ex-’: extraction, exhaustion, exclusion, and extinction engrave the Blue Marble’s surface, creating an image of a spectacular but alien Other.[3]

From epic drone shots of ice calving to dazzling photographs of oil spills, artists interpret the Anthropocene using the visual language of landscape extraction. In The Verifiable Image of the World, Bruno Latour points out that we see our planet “(…) from the outside-in, as if we were imprisoned in a raucous space station (or sitting on the throne of God), that we have completely forgotten to what extent this astronomical image of the world poorly reflects the common habitat shared by the living.”[4] Such a bird’s-eye perspective[5] accustoms humans to ecological disasters through horrifying yet sublime representations. This distancing detaches the spectator from the spectacle, but the toxic tongue-tailings, open pit mouths, and oil spills’ lazy eyes still look back.[6]

Jean Paul Getty, the American-born British industrialist who established the Getty Oil Company in 1942, famously said, “the meek shall inherit the earth, but not the mineral rights,”[7] subverting the biblical promise that the oppressed will receive the land. Subsequently, his grandson, Mark Getty, recognized that mineral and image extraction share the same economic liquidity and thus established Getty Images, the most extensive visual image stock collection. Nowadays, photography not only enforces the epistemic bias of dominant power regimes but also aids in capitalist accumulation via operational images.[8] Satellite mapping, drone filming, and military surveillance continuously deploy the camera shutter, the device that Ariella Aïsha Azoulay has called the ‘synecdoche of imperialism.’[9]

A shutter is a mechanism in a camera body that regulates the length of exposure of photographic film or a photosensitive digital sensor to visible radiation. In Potential History: Unlearning Imperialism[10] Azoulay advocates exploring the “dormant potentialities in the shutter’s exclusions, restrictions and differentiations.”[11] She suggests that drawings or re-enactments of the unphotographed events are essential to bridge the gaps in historical representation. The proposal to interpret silences and speculate on omissions resonates with what Saidiya Hartman termed ‘critical fabulation,’ a storytelling technique that disrupts colonial metanarratives.[12] As a designer and filmmaker, I argue that artists can refuse the violence of turbo-capitalism by challenging the technological conditions of image registration. To question ocularcentrism, an epistemological bias favoring vision over other senses, we must reconfigure the shutter to perceive beyond optics.[13]

Visible light occupies only a part of the electromagnetic spectrum, which also includes radiation such as radio, microwaves, infrared, ultraviolet, X-rays, and gamma rays. I capture these spectral presences by repurposing scientific devices and embedding them as prosthetic extensions in my camera rig. These custom technological pieces read information archived in the landscape[14] that is otherwise invisible to the human eye. In Slick Images: The Photogenic Surface of Disaster, Susan Schuppli reports that “we have (…) entered a new geo-photo-graphic era in which planetary systems have been [reshaped] into vast photosensitive arrays that are registering and recording the rapid transformations induced by modern industrialization and its contaminating processes.”[15] Nature’s agency in producing images[16] positions the filmmaker’s body, extended via prosthetic sensors, as a shutter or a catalyst in cinematic capturing of the flow of matter. In this Matter Theater, geological events shape film grammar, calibrating the aperture to the solar zenith angle, adapting the shutter speed to slow geological timescales, setting the frame rate to follow the planetary rotation, and examining false-color renderings for the spectral presences of the past.

Considering the above, the subsequent two case studies, Hard Drives From Space and Stones Talk, are examples of Matter Theaters, reflecting on knowledge production through cinema and effects of reconfiguring the shutter beyond vision.

Hard Drives From Space

Between 2020 and 2022, I directed, with Louis Braddock Clarke, the body of work Hard Drives from Space.[17] In this project, the shifting of magnetic values in iron meteorites became an anti-colonial strategy to restitute looted geo-matter[18] and facilitate the resurgence of Indigenous stories. In our quest for a climate-conscious production,[19] we traveled with local hunters across Inugguit Nunaat (Northern Greenland), a remote tundra marked by military operations, mining ventures, and meteorite craters. For centuries before the Iron Age, the Inuit crafted their tools from the extraterrestrial metal they called Innaanganeq.[20] However, during Danish colonization and the 19th-century North Pole expeditions, the meteorite pieces found their way to museums in New York and Copenhagen. Alongside mineral trophies, the Inugguit people were relocated and disgracefully displayed as a living ‘human zoo.’

The ‘speculative stones’ produced through geo-hacking, a process of altering the properties of materials, are one of the project’s outcomes. Louis and I organized community happenings in Inugguit Nunaat and scientific experiments at the Paleomagnetic Laboratory in Utrecht to re-magnetize the samples of the Innaanganeq meteorite, the eponymous ‘hard drives from space.’ By applying heat, local hunters erased the locked-in data indexing the temporality of colonial conquest,[21] simultaneously overwriting each piece with a new magnetic history.[22] This transformative process continued at the Paleomagnetic Laboratory, where Dr. Lennart V. de Groot measured the forces of attraction and repulsion saved in ‘speculative stones’ and inserted them in an array of new samples. In this way, the Innaanganeq meteorite immaterially returned to the landscape, sparking a debate among the Inugguit and researchers about the ownership of minerals from outer space.

The reason for geo-hacking the meteorites rather than physically restituting them goes beyond apparent limitations such as weight and legal status. Shifting magnetic values in stones finds its precedent in Indigenous cosmology, which animates the landscape as a breathing system. According to the Inugguit, the ‘breaths,’ or spirits, of all living beings are borrowed from hila, translating into the weather, climate, consciousness, and mind. At the moment of death, bodies return their ‘breaths’ to the landscape. This exchange of spirits portrays nature as one living organism, a network of connected parts.

In Inugguit Nunaat, people experience the cycles of life and death daily: at the edge of the sea ice (moving up and down, inhaling and exhaling), at the breathing holes,[23] on dog sleds, and in kayaks. Traditionally and still to this day, the Inugguit use iron harpoons for hunting sea mammals. According to a myth recorded in 1929 by the Greenlandic–Danish anthropologist Knud Rasmussen, “the spirit of a seal resides in the harpoon head for one night after the seal has been killed.”[24]

For the Inugguit subsistence hunters, this everyday hunting tool is not a weapon but a device that facilitates the passage of breaths from one body to another, emphasizing a profound sense of connection. The contemporary Norwegian ethnographer Hans Christian Gulløv describes a harpoon as “a medium of continuity between living beings.”[25] Perhaps by making harpoon heads out of extraterrestrial metal, the Inugguit sensed the capacity of iron meteorites, ‘hard drives from space,’ to lock in magnetic data.

The Inugguit’s understanding of the interconnectedness of all living things, as represented by the concept of invisible hila, finds a scientific analogy in geomagnetism. In Hard Drives From Space, the critical part of the process involves using custom-made microphones, or ‘geo-tools,’[26] which detect magnetic anomalies caused by climate change, mineral displacement, and other natural and artificial processes, such as geo-hacking. This data is then amplified into an audible spectrum, allowing one to listen to the landscape’s expression. Through these combined lenses of art and science, the viewer can immerse in geology’s spectral polyphony.

During a kaffemik[27] on Meteorite Island, Louis and I asked the local community whether they wished Innaanganeq fragments from Western museums had returned to the Arctic landscape. Historically, the cultural significance of extraterrestrial metals has spread beyond the craftsmanship of hunting objects. The Indigenous people anthropomorphized and animated the meteorite pieces, giving them names such as Woman or Dog, thus incorporating the celestial beings in local folklore. On the other hand, the law indicates that any natural treasure trove found in the Danish Realm, including Greenland, is considered state property; thus, the finder must deliver it to the National Museum of Denmark. Critical of this post-colonial policy, all kaffemik participants responded positively to the question of restitution. However, one person mentioned that the stones belonged to no one as they arrived from outer space. The Inugguit people hold a unique perspective on natural resources, refusing to consider them in terms of property or profit. Instead, they view them as a process of participating in the landscape, where property rights give way to user rights. This mentality, however, is challenged by colonial and post-colonial bureaucracy and its infrastructures. The Inugguit’s approach ensures that everyone benefits from hunting grounds, as they catch only what they need for their community, leaving the plentitude of resources to others. Inugguit geographical names reflect the mode of being in the landscape by indexing weather phenomena and hunting potentials.

On the contrary, the equivalent Western toponyms honor praiseworthy individuals who explored or conquered the land. For example, Oqqorliit, which translates into “shelter from the southwest wind,” became Inglefield Gulf, named after British explorer Edward Augustus Inglefield); Uummannaq, the ‘heart-shaped’ or ‘love-giving,’ indicating the abundance of animals, is now called Dundas, after British statesman Robert Dundas; and Qeqertarsuaq, a ‘large island,’ refers to Herbert Island, named after the Irish adventurer and writer Marie Herbert. Rather than merely referencing a territory, the Inugguit nuna encompasses “the land, the sea, the sea ice, and the memories, stories, and narratives bound up in the local environment.”[28] The landscape embodies the language.

In Some Ethnolinguistic Notes on Polar Eskimo[29], Stephen Pax Leonard points at the pervasiveness of the so-called ‘performative utterance’ in Inuktun, the language of the Inugguit spoken by less than eight hundred people. According to Stephen C. Levinson, in linguistics, “performatives are utterances that do not just say something—they actively change the reality they describe.”[30] For example, the Inuktun word for the sun, heqineq, comprises heqi, meaning ‘to splatter, to splash outward,’ and neq which signifies ‘the action of.’ Thus, the solar sphere of hot plasma, radiating energy from its surface, escapes categorization as a countable noun and instead becomes a verb. Rather than an object, the sun is an action. Heqineq is, hence, an example of the dynamic character of Inuktun, an agglutinative language where meaning occurs while one utters. This active disposition of Inuktun responds to the changing weather and live geology, showing the human entanglement with nature.[31]

Stones Talk

While Hard Drives From Space involved artificially shaping mineral magnetism to restore Indigenous histories, my solo work Stones Talk[32] unlocks the narratives sealed in the archive of matter through spectral archaeology. This expanded cinema project explores magnetic anomalies found in barrigones, giant potbelly sculptures made by the ancient people of Monte Alto (today’s Guatemala). The 2019 scientific discovery suggests that “(…) an understanding of magnetism existed in Mesoamerica, possibly pre-dating the ancient Greek descriptions.”[33] Before Europeans observed forces of attraction and repulsion between a magnetite-rich lodestone and iron fragments, the ancient Monte Alto people created complex sculptures with shapes and features that followed the magnetic fields of the rocks.

By running a magnetometer[34] over the carvings, scientists were able to pinpoint strong signals emanating from the belly buttons of the stone giants. Several of the barrigones consistently displayed magnetic anomalies in their umbilical zones. The deliberate nature of this pattern serves as evidence that the Monte Alto artists were not only aware of magnetic fields, but could also skillfully integrate the attractive force into their potbelly designs. A plausible scenario suggests that basalt boulders had been magnetized by a strike of lightning before they had been crafted. This implies that the ancient Mesoamericans traversed the terrain, reading the rocks for traces of the earthly allure. They used their lodestone stethoscopes to detect strong signals in boulders and further modify them into the navels of the potbelly giants. To quote Eva Barbarossa in Magnet, the ancient Monte Alto people aligned their civilization with earthly currents rather than the stars.[35]

Perhaps the swollen bodies of barrigones were crafted to commemorate the dead, with magnetic interactivity representing a lingering life force.[36] According to Roger Fu, one of the scientists conducting the study, “(…) the ability of these sculptures to deflect a compass in real time would have looked very impressive to an audience, giving the illusion of persisting life in these objects.”[37] Whether the magnetic navels served to honor ancestors or to reinforce political power is yet to be discovered. In Foucault’s Pendulum, Umberto Eco uses the symbol of the umbilical cord of the Earth to represent a geographic position from which one can control all global powers: “the critical point, the Omphalos, the Umbilicus Telluris, the Navel of the World, the Source of the Command.”[38] The Geomagnetic North Pole in the Arctic is an example of such a place with intense magnetic activity. Coincidentally, the Inugguit word for the North Pole, qalaherriaq, means ‘a big belly button.’ The naming probably originated from looking at a map with concentrated latitudes during the 19th-century expeditions to the top of the world. The Inugguit jokingly ridiculed the obsession of white explorers with the big navel, where one can find nothing but ice.

The same colonial impetus determined the fate of the barrigones. In the 1840s, a settler family du Teil of French nobility acquired La Concepción, a farm in Guatemala’s Escuintla, transforming it into a coffee business.[40] While clearing the land to sow exotic coffee bushes, the workers found the ancient potbelly giants aligned in an architectural ensemble. The landowners promptly embezzled the sculptures, which allowed them to sell the pieces to Friedrich Ludwig Werner von Bergen, the German ambassador to Guatemala, and Amour-Auguste-Louis Joseph Berthelot, a French nobleman. Tucked among sacks of coffee, the barrigones set out for Berlin and Paris to “(…) nourish the cellars of the great museums—showcases that made public the hegemony of the European powers in the world.”[41] Similarly, the archaeological site remains a part of the plantation with limited access for visitors.[42]

Studying the potbellies, the international group of scientists gathered proof that the ancient Monte Alto civilization had known of magnetism possibly before the Greek philosophers described the phenomenon of the attractive force. Roger Fu points out that “there is a perception that the Old World is the advanced world and transferred all this knowledge to the New one, but we are realizing that they knew a lot, and I think this is one more piece of evidence for that.”[43] The proof, invisible to the human eye and obtained virtually through scientific mapping, sheds new light on the ocularcentric knowledge paradigm in Western culture.[44] Whereas European colonists and settlers charted the landscape with maps, drawings, chronicles, instruments, documentations, signs, and writing, the wisdom of ancient Monte Alto people haunts from beyond the perceivable.

In my artistic research, scientific knowledge comes into dialogue with Indigenous wisdom rooted in nature. Science perceives the environment “(...) in visual terms of a space and a time that are uniform, c,o,n,t,i,n,u,o,u,s and c-o-n-n-e-c-t-e-d.”[45] Marshall McLuhan argued that such linear sequencing of concepts laid the groundwork for Western rationality and logic, which are the pillars of the scientific method.. On the other hand, when I was traversing Melville Bay with Inugguit hunters in search of the meteorite craters, the landscape presented itself as timeless and boundless. We would often detour for days to hunt, cache meat, prepare meals, tell stories, and sit in silence. In these moments, the midnight sun created a perception of temporality inherent to natural cycles and slow geological timescales, whereas the thick fog blurred the horizon and perspective lines. This experience forced the controlling nature of the eye, the dominant organ of sensory and social orientation, to give way to the magic world of the ear. To paraphrase McLuhan, we were given “an ear for an eye.”

In Monte Alto, the ancient sculptors performed breaks in the flow of stone; they saw the mineral as moving matter, untamed by the categories of time or concepts like electrons or atoms.[46] Their rock readings bulged into giant loggerhead turtles with magnetic beaks, who navigate via the magnetic fields, sensing them in four dimensions. The pre-Colombian artists could tune into the landscape without dividing, objectifying, or categorizing it. “There are things whose name cannot be mentioned; actions which precede language, names, meanings; desires which resist being recorded; instinctive, irrational, human moments. There are things that happen that exist outside cultural constructions,” observes the narrator in Carlos Motta's Nefandus[47], an audiovisual trilogy investigating pre-Hispanic ways of knowing. The character, searching the Colombian landscape for clues of untold stories, reflects on the “imposition of European epistemological categories during and after the conquest of the Americas.”[48] He juxtaposes a mode of being in the world with the one representing it, the latter referring to the colonial objectification of the world:

“The landscape does not confess what it had witnessed, [whereas] the images are out of time and veil the actions that have taken place there. If we watched attentively the current of the river, the foliage of the trees, or the weight of the rocks, would that reveal their history?” In Material Witness: Media, Forensics, Evidence,[49] Susan Schuppli argues that matter may record external events, bear witness, and provide evidence of occurrences otherwise unperceived. For example, the zoomorphic surface of ‘disaster film’ produced by the DeepWater Horizon oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico provides proof of capitalist process with chains of commands spread in time and space, too vast to be perceptible for human beings.

Conclusions

Matter Theater gives a platform to stories enchanted within the landscape. From an anthropological perspective, Justin Armstrong refers to it as ‘spectral ethnography.’[50] This subjective inquiry is preoccupied with “an anthropology of people, places, and things that have been removed, deleted, and abandoned (…).”[51] His theory is inspired by Jacques Derrida’s hauntology,[52] which engages with the ghosts of colonialism, looking closely at the spectral presences of what only seems to be forgotten. Armstrong proposes a strategy of browsing through the accumulated layers of time and materiality in search of narratives that emerge from what had been discarded. This approach poetically references the methods used by paleomagnetic scientists who read terrains with magnetometers.

Inside the Earth, a hot, molten metal mixture of iron and nickel is in constant motion. This movement, like a natural geodynamo, generates magnetic fields. When volcanoes erupt, lava crystals lose their magnetization; upon cooling, they save new magnetic properties inherent to time and geolocation. This unique property makes the strata of lava crucial data storage devices for mapping the history of earthly magnetism. Similarly, iron-nickel meteorites, with their equivalent physical properties, can lock in magnetic information. In that sense, stones are not only witnesses to extraction and exploitation, but thanks to their transformative powers, new theories can be formulated, and histories can be written. Stone is everything but “equal to itself | obedient to its limits | filled exactly | with a stony meaning.”[53]

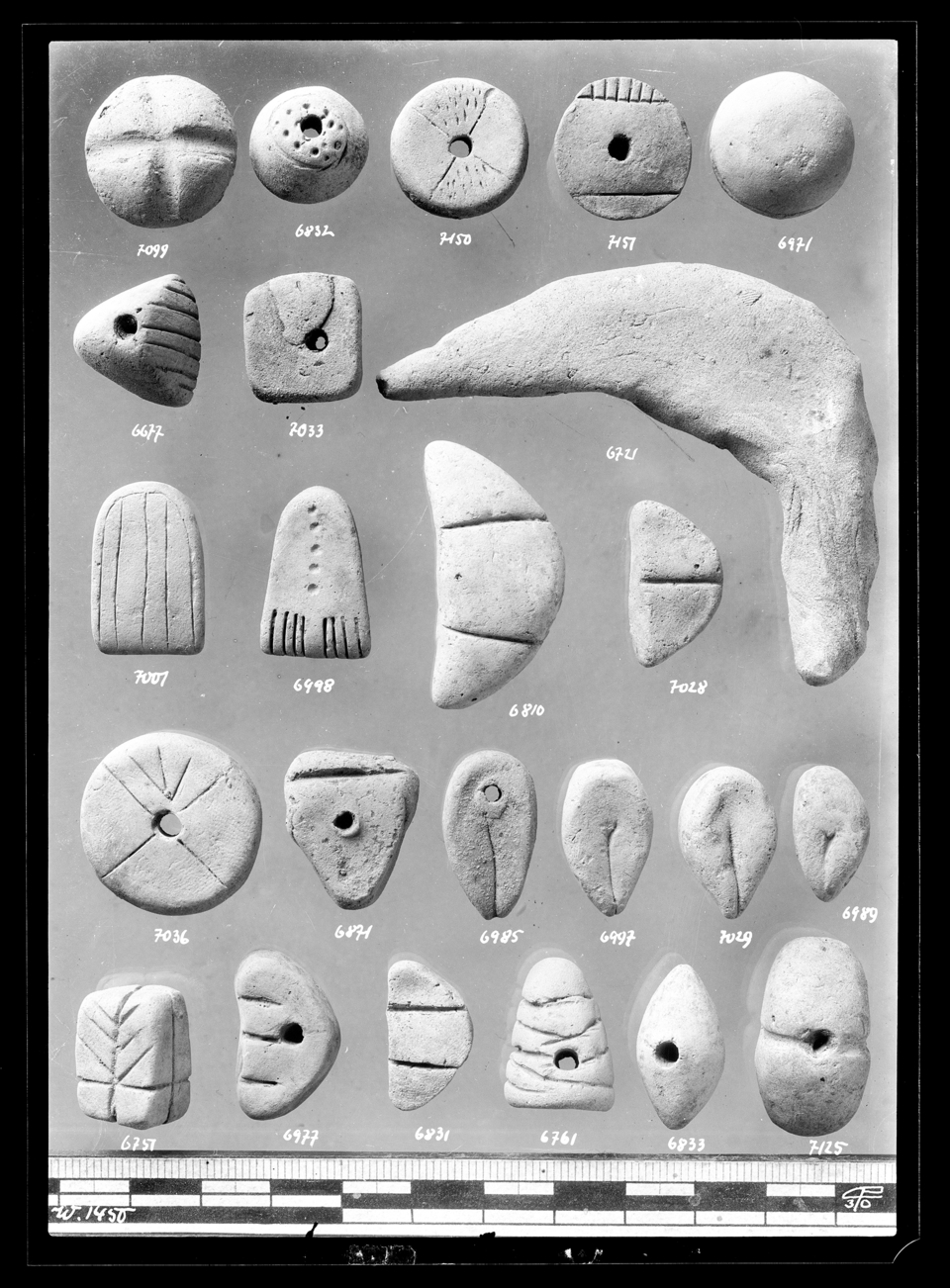

1. Examples of ‘tokens,’ miniature clay counters from ancient Sumer. Courtesy of German Archeological Institute.

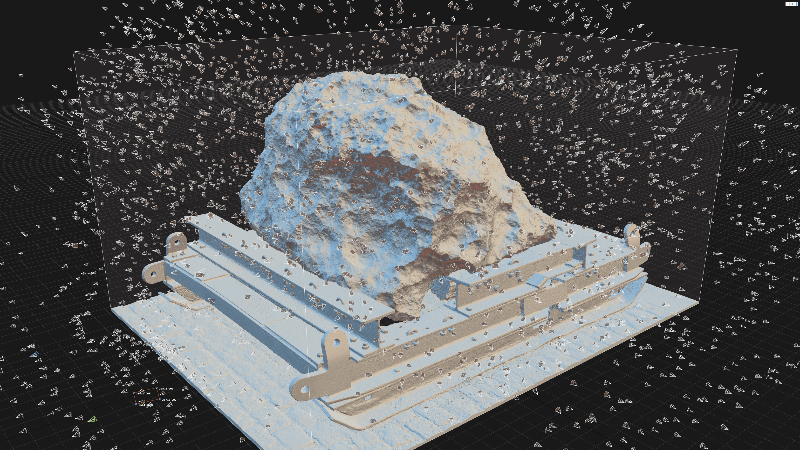

2. ‘Agpalilik’ (Innaanganeq Meteorite) at the National Museum of Denmark, situated on the original sled used for extraction. Out of Focus. Directed by Louis Braddock Clarke and Zuzanna Zgierska, 3D scan by Rigsters, director’s cut, Video Power, premiere in 2025.

3, 4. Rewriting: With a blowtorch, a 9.8 g sample of ‘Arnakitsoq’ (Innaanganeq Meteorite) has been heated above Curie temperature. The process was performed at the crater by the Inugguaq hunter and rock ‘n’ roll musician Aleqatsiaq Peary, whose great-great-grandfather extracted the meteorite in 1897, taking it to New York. Through this gesture, Aleqatsiaq Peary erased the stone’s magnetic history. On an alchemical level, the colonial weight is lifted, triggering a new opening. Out of Focus. Performances by Olennguaq Kristensen and Aleqatsiaq Peary.

5. Rewriting 2: Hunters from Haviggivik rewrite magnetic data of the ‘Agpalilik’ (Innaanganeq Meteorite) fragment. Out of Focus. Performances by Olennguaq Kristensen, Karl Halsøe, Ilannguaq Jeremiassen, Qillaq Nielsen, Ole Nielsen, Jenny Nielsen, Nuka Kristensen, Naduk N. Kristensen, Atugsuk Suersaq, and Jeremias ‘Minik’ Nielsen.

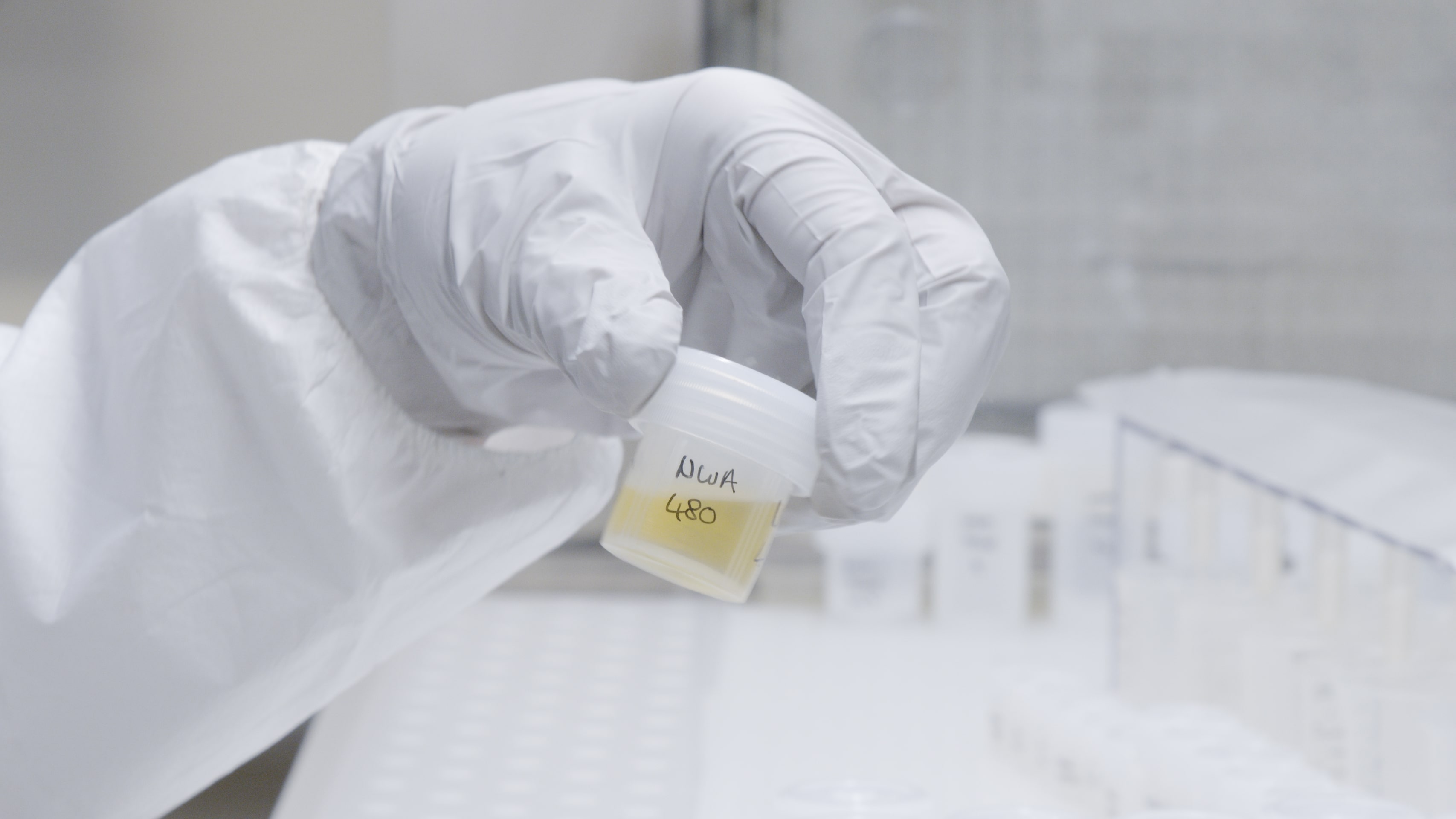

6. Storing: A 17.5 g sample of ‘Agpalilik’ (Innaanganeq Meteorite) has been remagnetized to the geomagnetic value obtained from the ‘Arnakitsoq’ fragment that had previously undergone Rewriting (see above). In this experiment, the induction coil of a thermal demagnetizer continuously applies 58.650nT as the iron stone is procedurally heated to 1000°C. Out of Focus. Performance by Dr. Lennart V. de Groot, Assoc. Prof. Paleomagnetic Laboratory, Utrecht University.

7. Erasing: A 0.1 g sample of ‘Agpalilik’ (Innaanganeq Meteorite) has been dissolved in 6M HCl. The yellow plasma solution is used for scientific measuring. As a side effect of such investigation, the meteorite vanishes into thin air, re-entering the atmosphere. Out of Focus. Performance by Prof. Martin Bizzarro, Director StarPlan (Centre for Star and Planet Formation).

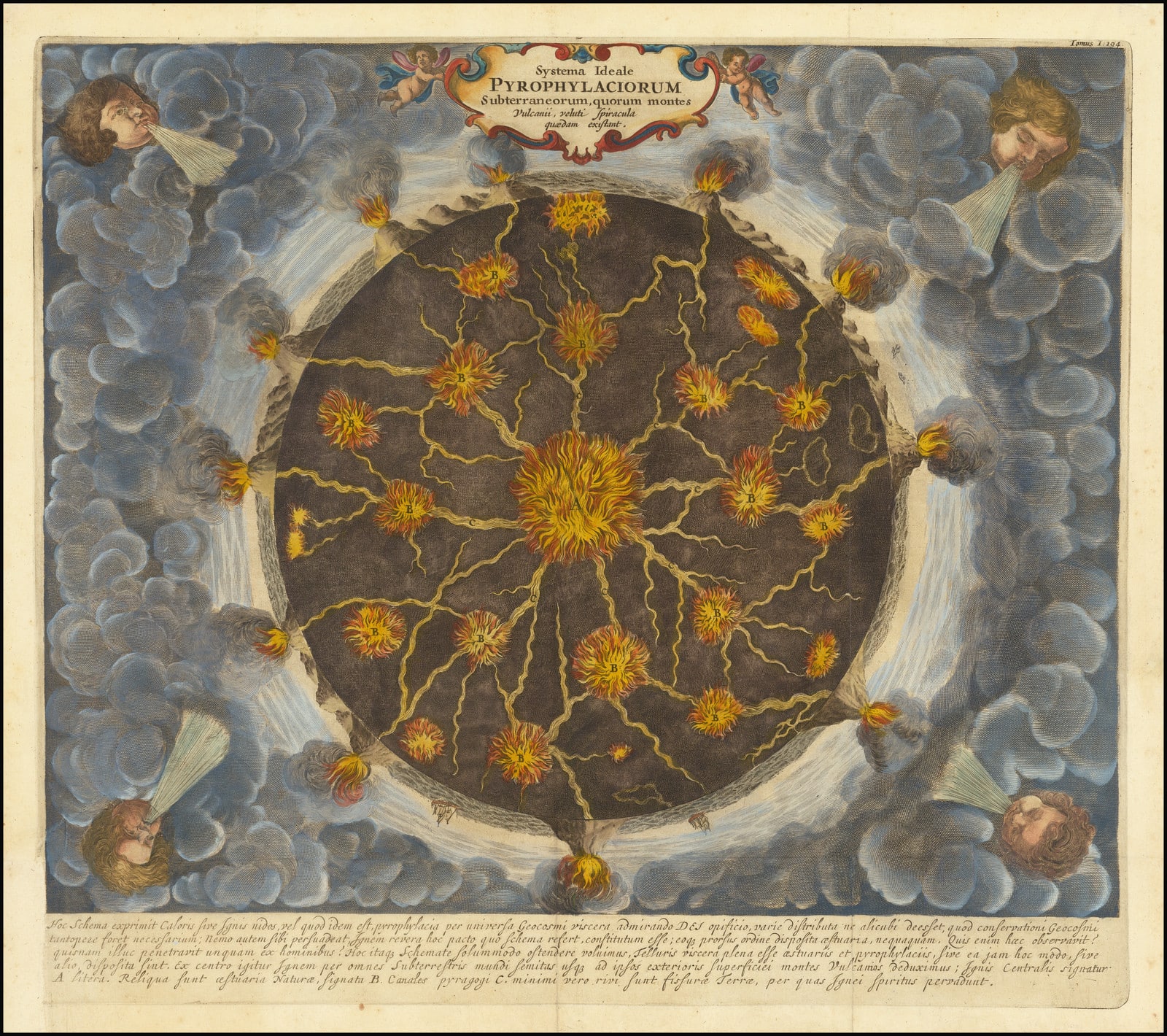

8. Athanasius Kircher, Systema Ideale Pyrophylaciorum Suberraneorum, quorum montes Vulcanii, veluti spiracula quaedam existant, 1665.

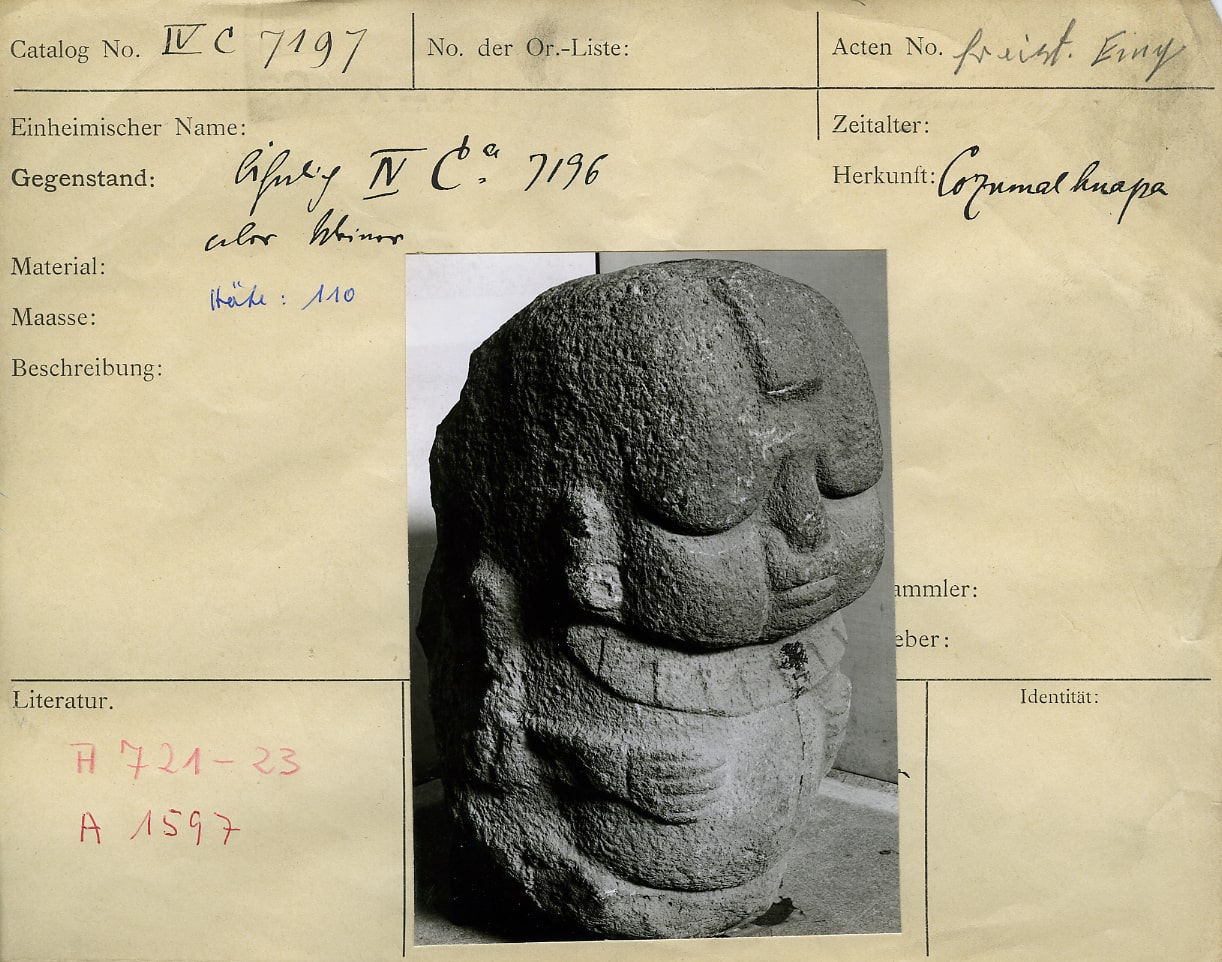

9. Barrigón, Late Preclassic Maya, 500 BCE – 300 BCE. Berlin State Museums, The Ethnological Museum of Berlin / Ines Seibt CC BY-NC-SA 4.0.

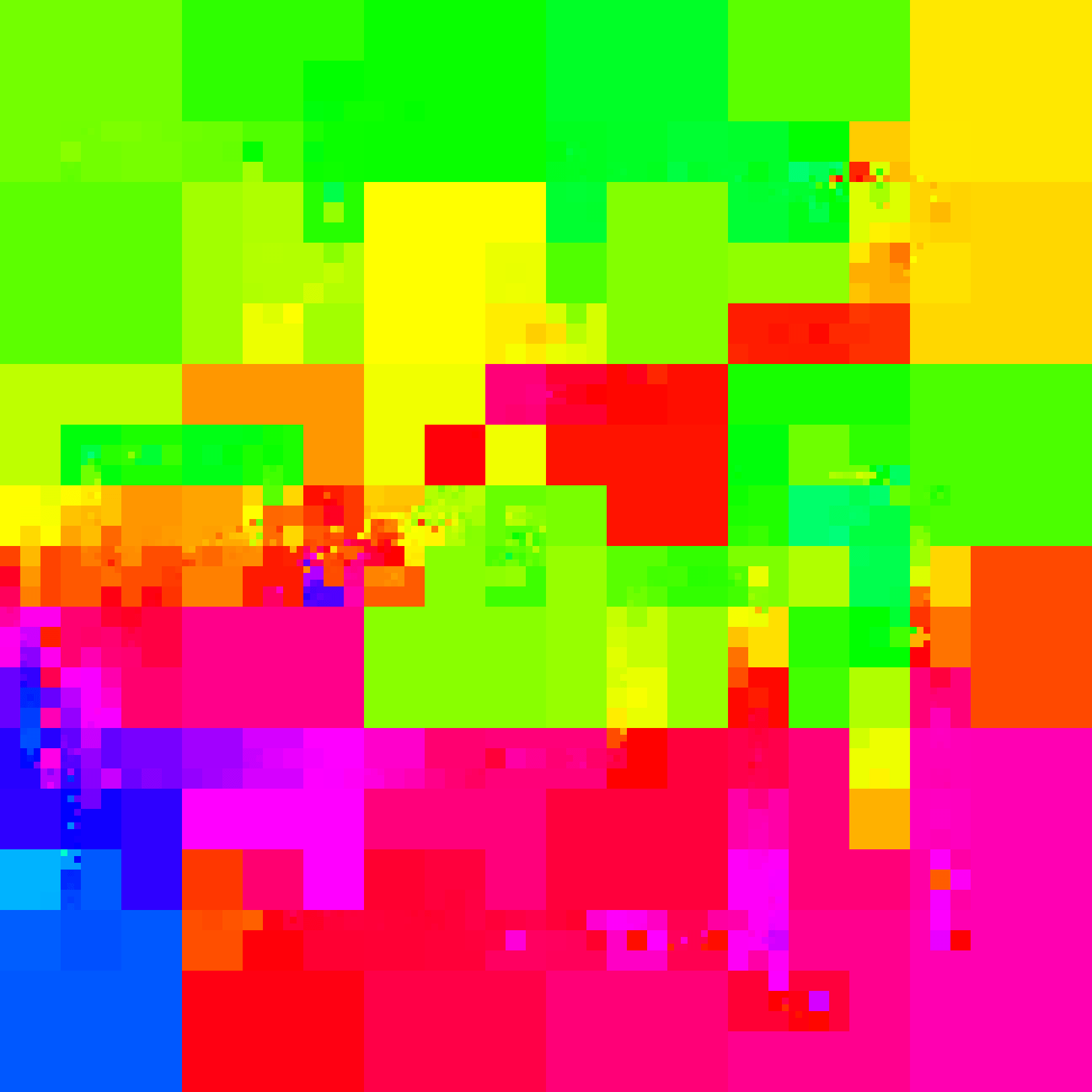

10. A spectrogram generated by a custom-made hand-held 3-axis magnetometer with fluxgate sensors. © 2024 Zuzanna Zgierska. Produced with Ronald Vester and Louis Braddock Clarke.

Biography

Zuzanna Zgierska (she/her) is an artist-researcher and filmmaker working at the intersection of ArtScience, Transmedia Storytelling, and Digital Culture. Her artistic practice is driven by the need for critical narratives in the age of ‘ex-’ (extraction, exclusion, and extinction). She untangles the planetary tongues through fieldwork, geo-hacking, and cross-cultural exchanges. From Earth Simulation Lab to the North Pole, Zuzanna creates landscape imaginaries by connecting scientific research with Indigenous wisdom, challenging the existing knowledge paradigms.

She teaches artistic research at the Royal Academy of Art, The Hague (BA academy-wide program), and design research at the Design Academy Eindhoven (MA Critical Inquiry Lab). Zuzanna is currently a Digital Culture Fellow 2023–24 (Netherlands Film Festival, Utrecht) and a member of “Politics of Knowledge” Research Group 2022–24 (Lectorate Art Theory & Practice, Royal Academy of Art, The Hague). Besides her appointments at art and design academies, she has given presentations worldwide at community centers, galleries, artist initiatives, film festivals, research institutes, science seminars, and as part of radio shows.

Zuzanna received a Talent Award 2024 (Creative Industries Fund NL), a Golden Calf in Digital Culture 2022 (Netherlands Film Festival), and a Landscape Research Award 2021 (Landscape Research Group UK). Her cinema-expanded and installation works have been shown at international festivals and galleries, including Sonic Acts Biennial (Amsterdam), Netherlands Film Festival (Utrecht), Digital Art Festival (Taipei), Noorderlicht International Photo Festival (Groningen), W139 (Amsterdam), MU Hybrid Art House (Eindhoven), and Stroom (The Hague). She has a studio at Quartair Contemporary Art Initiatives in The Hague, the Netherlands.

- Schmandt-Besserat, Denise [1996]: How Writing Came About.

- Hörl, Erich [2015]: The Technological Condition. Further, in Individuation in Light of Notions of Form and Information (1964), Gilbert Simondon criticizes the binary character of technical operations (such as one that uses clay tokens, the ancient trade technology, imposed on nature by itemizing biological stock). Simondon notes that the dichotomy between form and matter or subject and object is akin to a city divided into citizens and enslaved people, thus instituting a social hierarchy.

- Blue Marble is the first full image of the Earth, taken by the Apollo 17 space mission in 1972. Seen as a whole, the globe became countable, calculable, comprehensible; isolated from human experience.

- Latour, Bruno [2019]: The Verifiable Image of the World.

- “The all-seeing gaze of reason, the abstraction and miniaturization of the real that was the prerogative of mapmakers and urbanists.” Vázquez Melken, Rolando [2021]: Vistas of Modernity: Decolonial Aesthesis and the End of the Contemporary.

- “Anthropogenic matter is relentlessly visual in throwing disturbing images at us from which we should recoil, were we not part of this same obscene metabolic order.” Schuppli, Susan [2015]: Slick Images: The Photogenic Surface of Disaster.

- Derbyshire, Wyn [2022]: Jean Paul Getty: The Meek Shall Inherit the Earth—But Not Its Mineral Rights.

- Harun Farocki coined ‘operational image’ around 2000, and Jussi Parikka recently described it in depth in Operational Images: From the Visual to the Invisual (2023). Operational images are images beyond representation, the outcomes of the expanding field of machine vision.

- Azoulay, Ariella Aïsha [2019]: Potential History: Unlearning Imperialism.

- Ibid.

- Van Laun, Bianca [2020]: Reviewed Work: Potential History: Unlearning Imperialism Ariella Aïsha Azoulay.

- Hartman, Saidiya [2008]: Venus in Two Acts. Growing up in Polish culture that employed aesthetic categories such as irony or grotesque to expose nuance and bypass censorship, the act of “reading between the lines” has been central to my artistic practice.

- While Azoulay argues that we must unlearn the shutter's authority, I propose reprogramming it instead.

- Armstrong, Justin [2010]: On the Possibility of Spectral Ethnography. Armstrong theorizes that the landscape accumulates cultural space and time (collective memory, regional imaginaries, and popular stories).

- Schuppli, Susan [2015]: Slick Images: The Photogenic Surface of Disaster.

- Asia Bazdyrieva and Solveig Qu Suess’s documentary project Geocinema (2020) employs “planetary-scale sensory networks as a vastly distributed cinematic apparatus,” while in Geological Filmmaking (2022), Sasha Litvintseva explores the entanglement of cinema with geology through minerals, metals, and chemicals “extracted from the ground often at high environmental cost.”

- The project continues as an expanded cinema production, with a premiere expected in 2025.

- “Two years ago, the Gonçalvez Commission recommended the unconditional return of looted colonial art. (...) It is striking that there is hardly any discussion about the biological colonial treasures and how they were collected.” Fresco, Louise O. [2022]: Vergeet de biologische koloniale schatten niet.

- The goal was to engage local people in production by avoiding post-colonial infrastructures and services. Gratification for all services and parties was determined on the basis of the Dutch Fair Practice Code, Dutch Diversity & Inclusion Code, and Greenlandic KNAPK (Qaanaaq Hunter Union).

- The Inuktun name Innaanganeq refers to what is known in the Western world as the Cape York Meteorite.

- Above the Curie point, iron stones lose their original magnetic information.

- As a sample of an iron meteorite cools down, it saves the geomagnetic conditions specific to time and space.

- Breathing holes are openings in the ice used for hunting and fishing.

- Rasmussen, Knud [1929]: Intellectual Culture of the Iglulik Eskimos. Report of the Fifth Thule Expedition 1921–1924.

- Gulløv, Hans Christian [1997]: The Soul of The Prey. Fifty Years of Arctic Research.

- The term ‘geo-tool’ was coined by Louis Braddock Clarke, the collaborating artist.

- Kaffemik is a traditional Greenlandic social gathering.

- Pax Leonard, Stephen [2015]: Some Ethnolinguistic Notes on Polar Eskimo.

- Idem.

- Levinson, S. C. [1983]: Pragmatics.

- Helen Palmer and Vicky Hunter describe such a relation as ‘worlding,’ which is “a particular blending of the material and the semiotic that removes the boundaries between subject and environment, or perhaps between persona and topos.” Palmer, Helen; Hunter, Vicky [2018]: Worlding.

- Stones Talk is a working title for the work in progress.

- Fu, Roger R.; Kirschvink, Joseph L.; Carter, Nicholas; Chinchilla Mazariegos, Oswaldo; Chigna, Gustavo; Gupta, Garima; Grappone, Michael [2019]: Knowledge of Magnetism in Ancient Mesoamerica: Precision Measurements of the Potbelly Sculptures from Monte Alto, Guatemala.

- A magnetometer is an instrument for measuring the magnetic field at a point in space.

- “Absent a written history, (...) we did not look for how our ancestors used the lodestone to create their civilizations. We looked to the heavens for alignment rather than to the Earth.” Barbarossa, Eva [2020]: Magnet.

- Rapp Learn, Joshua [2019]: Mesoamerican Sculptures Reveal Early Knowledge of Magnetism, Smithsonian Magazine.

- Fu, Roger R.; Kirschvink, Joseph L.; Carter, Nicholas; Chinchilla Mazariegos, Oswaldo; Chigna, Gustavo; Gupta, Garima; Grappone, Michael [2019]: Knowledge of Magnetism in Ancient Mesoamerica: Precision Measurements of the Potbelly Sculptures from Monte Alto, Guatemala.

- Eco, Umberto [1988]: Foucault’s Pendulum.

- Pax Leonard, Stephen [2015]: Some Ethnolinguistic Notes on Polar Eskimo.

- The telluric currents erupt from the core of the earth, nourishing the land. Guatemala has nutrient-rich volcanic soil, which was a magnet for colonists and settlers.

- Chinchilla Mazariegos, Oswaldo; Fauvet-Berthelot, Marie-France [2018]: De barones y barrigones: el periplo de las esculturas de Concepción, Escuintla.

- Information shared by Manuela Maria Girón Recinos, a producer and fixer I collaborate with, during a conversation on the phone.

- Reuell, Peter [2019]: The Mesoamerican Attraction to Magnetism.

- Ocularcentrism is a perceptual and epistemological bias ranking vision over other senses in Western cultures (Oxford Dictionary).

- McLuhan, Marshall [1967]: The Medium is the Massage. An Inventory of Effects.

- “When I perceive a table, the physicist has clearly explained to me that it’s electrons and atoms, yes, but a table, I do not necessarily grasp it as movement-matter. I have been told, or I can understand that a table is a break in a flow of wood, (...) but where is the flow of wood?” Deleuze, Gilles [1979]: Metal, Metallurgy, Music, Husserl, Simondon.

- Motta, Carlos [2013]: Nefandus.

- Torrens, C. [2024]: Conquered Rivers And Sexualities Denied.

- Schuppli, Susan [2020]: Material Witness. Media, Forensics, Evidence.

- Armstrong, Justin [2010]: On the Possibility of Spectral Ethnography.

- Ibid.

- Derrida, Jacques [1993]: Specters of Marx.

- Herbert, Zbigniew [1961]: The Stone.

Politics of Knowledge (2022–24), Lectorate Art Theory & Practice at the Royal Academy of Arts.