Rethinking Community

Introduction

After participating in the Royal Academy of Art The Hague KABK diversity group, experiencing the impact of the global pandemic and witnessing multiple crises concerning social safety at our Academy, Maarten Cornel and Ingrid Grünwald initiated ‘The Big Dialogue’ within the Graphic design department as part of the academic year 2020-2021.

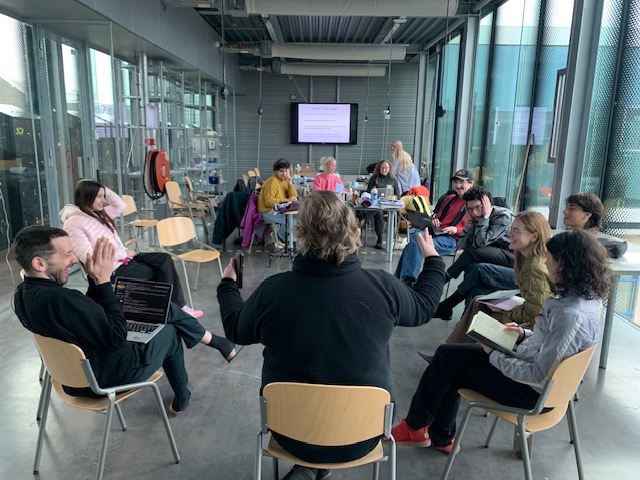

From 2021 to 2023, five dialogue sessions were held in the Graphic Design department and one in the Embassy of the Free Mind, attended by Graphic Design tutors and students. During these sessions we wanted to create a safe place for conversation and connection. Our goal was to address topics concerning the social safety of our international community, taking into account different perspectives and approaches on this matter.

One of our main drives was: How to contribute to a stronger community in times of fragmentation? Our dialogue sessions tried to unite the theoretical and the empirical. We studied relevant literature (philosophical as well literary). At the same time, we created space for learning by organizing open talks and opening ourselves up to whatever ‘could happen’.

Questions we were interested in concerned the particularities of self-expression with a need for clear and respectful communication. We considered: what does it take to listen actively (summarize what you have heard, ask open questions)?

The first international session we organized was at the Elia Biennial in February 2022 which focused on the issues we were facing within our Graphic Design Community concerning social safety, hierarchical imbalance, organizational crisis, student uprisings, and societal issues permeating into classroom dynamics. Our talk resonated with all participants, who were dealing with similar issues in their own academic contexts. Together with four participants from Marseille, Brussels and Glasgow, as well as one of our own tutors we decided to continue the dialogue after the conference. This connection resulted in an extra workshop together in the Elia Biennial in Helsinki: “The Board Meeting, based on a real story”, in which we brought in our own dilemmas as tutors, directors, coordinators, and curators. This dialogue will continue to develop as part of the Elia Biennial Conference in Milan in November 2024.

Moreover, we organized dialogue sessions in Europe as part of a follow up series (The Beaux Arts, Marseille; Le 75, Brussels and Athens School of Fine Art, Mykonos). Our research expanded through questions such as: How are other European art institutions dealing with their challenges? How does our format of ‘The Big Dialogue’ work in different contexts? How can we continue to transform whilst creating tools for conversation facilitators based on all of these experiences?

The Big Dialogue sessions are—with all their different approaches, methods and themes—our research method. In order to further articulate this, we consider: What is ‘brought to the table’ by the participants—students, teachers, staff—during these conversations, and what can we learn from this? And how do different dialogue methods contribute to forms of community building/connection?

Politics of Knowledge is all about power. How different, competitive, discourses define which views should prevail, as well as how social groups and organizations distribute, share and produce knowledge themselves. Knowledge influences our decision-making. Do we dare to speak openly (Parrhesia) and face the consequences? Knowledge, as Foucault has shown, always takes place in a network or system of power relationships.

What we acknowledge as true knowledge stems from what is accepted and defined as true by the groups involved. The Politics of Knowledge expands upon which knowledge(s) is accessible and usable for which groups. Brought to our KABK dialogue sessions, this practice deals with questioning the assumptions that constitute our ideas or thinking to create deeper understandings and see more potential.

A dialogue is ideally more harmonious than a discourse; it is a conversation between people, it is cooperative, it involves all participants, while a discourse is more centered around formal, directed debate. Ideas and initiatives need to be embodied and shared and we have seen how participation in our dialogues has not always been easy for participants, yet, it often has made them more acutely aware of their own ideas, their assumptions, and perspectives, as well as those of others.

The dialogue sessions challenge and stimulate individual agency, positioning, and a sense of responsibility. They also facilitate a collective space for exchange, where thoughts, observations, desires or frustrations, arguments or examples all contribute to the development of a common understanding of the subjects at hand.

Moments of reflection are rather rare in the rich and busy curriculum of an Art Academy, but highly beneficial to personal and communal development. Reflection can provide insight; dialogue or self-expression can therefore be cathartic. An importance should be placed on ensuring that there are moments like these, in- and outside of the curriculum.

When we are in dialogue with each other there is connection, and from connection community grows. Our community should celebrate its rich cultural and social diversity. Listening to each other and addressing each other openly but respectfully can be a tool to revitalize fertile connections. Understanding supports open-mindedness.

The two following essays present the core of our experiences in organizing ‘The Big Dialogue’. The first, by Drs. Maarten Cornel, Teacher of Philosophy at Graphic Design Department, lecturer and group teacher at the Academy Wide Program Common Ground reflects through a theoretical lens, and the second by Drs. Ingrid Grünwald, Senior Coordinator of the Graphic Design Department, focuses on a linguistic and communicative frame for our dialogues.

Big Dialogue in the Gipsenzaal KABK with students and tutors 2022

Big Dialogue in Beaux Arts Marseille 2022

Reflecting on and contextualizing ‘The Big Dialogue’ sessions.

By Maarten Cornel

Introduction

In his book Event, first published in 2014, Slavoj Zizek, quoted Franco Bifo Berardi, stating that the rage exploding all around Europe today is:

“impotent and inconsequential, as consciousness and coordinated action seem beyond the reach of present society. Look at the European crisis. Never in our life have we faced a situation so charged with revolutionary opportunities. Never in our life have we been so impotent. Never have intellectuals and militants been so silent, so unable to find a way to show a new possible direction” (p.181).

This was published ten years ago. Ten years later, in 2024, the situation is no less complex. On the contrary, a world wide pandemic, inflation, identity politics, ongoing changes in climate, shifting geopolitical situations caused by, amongst others things, a war in Ukraine and escalation of the conflict between Israel and the Palestinian territories, have not brought a sense of stability, interconnection, or new possible directions.

This situation has unavoidably impacted mass populations, no matter their position, creating core (social) challenges. The anger and powerlessness that was spoken about in the above quote can also be experienced and felt in many educational settings. There are no clear solutions to many of these hyper complex topics and issues. Often, discussions result in more polarization than interconnection or shared attempts to find solutions that benefit (most) people involved.

In 2021, Ingrid Grünwald (coordinator), and Maarten Cornel (Philosophy teacher) of the graphic Design department at the Royal Academy of Art, The Hague, came with a plan to set up sessions of dialogues, called ‘The Big Dialogue’. The term ‘big’ refers to the big challenges and the bigger frame of most of the subjects involved. In an attempt to provide space to share ideas, express anger or concern, observation, and pose questions, multiple dialogue forms were chosen. In this essay, there will be a short overview of these methods, embedded in a wider general reflection. Next to this, I will share some different terminologies and concepts that have inspired us in setting up ‘The Big Dialogue’. Some of these terms, such as ‘parrhesia’, ‘soft skills’, ‘moods’, and ‘narratives’, which will be discussed in more detail below.

A dialogue is a two or multiple way, cooperative conversation, different from a debate or wider discourse. Having seen how full school curricula are with little space there for reflection, or meta-narrative study on all matters involved in the educational and social processes, a dialogue as a meeting place is what we envisioned as an alternative. We had many considerations: How to best make space for interconnection? How to make this a collective investment? But also: What is a reasonable outcome of, or expectation for a dialogue? In the end, experiencing the many facets of both facilitating and participating in a dialogue itself became part of the ‘outcome’. How to keep it ‘small’ yet truthful? How to position ourselves in addressing subjects that relate to community/bubble? We in no way wanted to preach any kind of ideologies, yet, within our international setting at our Academy, it was imperative that we explore different ideas and viewpoints on the topics at hand. Diversity in itself is not always fruitful unless it is made visible and relatable.

It might seem rather ambitious to think that dialogues can even contribute to overcoming the big challenges that confront us, and it can also be seen as naive idealism. But we are already surrounded by a landscape of skepticism and cynicism, and surely we cannot expect solutions from such stances?

Such methods require courage to ‘embody’ ideas, preserving integrity, creating laughter (laughter binds) and communal acceptance (harmonizing insights). Good intentions are not enough for any dialogue alone, it needs investment and embodiment.

So, this following essay will be reflecting on theoretical concepts and other aspects central to our experiences of ‘The Big Dialogue’.

1. Knowledge(and power)

We started our sessions of The Big Dialogue before joining the KABK Research Group “The Politics of Knowledge”. Our participation in this group gave us the chance to develop, refine, and compare our methods. It also changed the second part of our original experiment, diversifying the methods and forms of dialogue as a consequence of having studied even more theoretical and practical documents. On the whole, we are very aware that every dialogue is a co-creative event. Agency doesn’t just mean the capacity to speak out, or speak well. Agency also deals with self-awareness and inner transformation. Listening to others also contributes to agency. Thus, participating in this Research Group gave us the time to read, analyze, compare and expand our initiative and set it in a broader frame, conceptually and practically.

We have always seen ‘The Big Dialogue’ as an attempt to create a free place where ideas and observations can be shared and possible actions can be envisioned and talked about. Politics is not just about government, but about how we repeat, confirm, or question certain norms in daily life. Michel Foucault emphasizes that power is everywhere:

“Power is not something that is acquired, seized, or shared, something that one holds on to or allows to slip away; power is exercised from innumerable points, in the interplay of non egalitarian and mobile relations’ (From History of Sexuality, P.94).

Power comes from ‘below’. Power relationships are intentional and non subjective. Relations of power are immanent in the other relationships such as economical, knowledge relationships or sexual relationships. Where there is power, there is resistance, however this resistance is never ‘in a position of exteriority in relation to power’.

Can we conceive of a dialogue uniting a sense of wonder and knowledge sharing? One where power play is kept at a low? Or is that too much to ask? What would be needed in order to deal with this, in case power play is unavoidably part of any dialogue? We have always striven as facilitators, to avoid any power games or power play during our dialogues. We wanted to be as much like the fellow participants, in terms of our input, actions and behavior, as possible, outside of only offering a frame. As Foucault expresses:

“Confession frees, but power reduces one to silence; truth doesn’t belong to the order of power, but shares an original affinity with freedom” (From History of Sexuality, P.60).

Knowledge is power, persuasion is power, clarification is power. But the complex dichotomy between critical thinking, saying what you think, and taking into account social and communal well being through empathy is at the core of what this text wants to explore. If power relations, or any human relations are interdependent and contingent, what promise lies in this changeability, or chance?

I will first talk about contingence, and continue thereafter presenting Foucault’s discussion of parrhesia, concluding this first part with a reflection on how this can relate to ‘The Big Dialogue’.

1.1. Contingency

In this paragraph on contingency, I want to introduce three (different) terms: contingency, moods and ground, and connect them as important factors that any dialogue and human exchange can be marked by.

Firstly, ‘contingency’. This term has many meanings and implications. It deals with the unforeseen; things that are unpredictable, or accidental. Contingency also means circumstance and chance. ‘Eventuality’, as a term, might come in handy later. Yet, philosophically speaking, the term also means ‘possibility’ from the Latin contingentia (possibility, chance). Things that exist could have been different as well, contingency is not necessary for dealing with what is possible. Contingent things are dependent on their surroundings and could have just as well been different as a consequence. Incidents are part of life and shape our reality, and that situation is contingent. Contingency is the opposite of necessity. Richard Rorty, in his book Contingency, Irony and Solidarity (1989), has suggested that contingence is the condition pur sang, yet, if contingency exists, is contingency necessity?

The second term is ‘mood’, not to be fully similar like terms as emotion or pathos. Though it arguably took philosophers 2500 years to theorize the fact that humans have moods and these (pre) dispositions that influence all of our thoughts, acts, choices and communication, it was Martin Heidegger in Sein und Zeit who discussed ‘Stimmung’, a.k.a mood. A very important reality and basic condition for any inter-connective initiative experience, like a dialogue, is this unavoidable and changing basic condition. Our moods are fundamental dispositions of affect that shape how we perceive all existing things. Dasein (being there) is a human condition, and with this condition comes this position of our being. We are ‘being’ and we are our ‘way of being’ at the same time. This mode of being disposed, as described in Sein und Zeit by the related term Befindlichkeit, is of direct influence in how we understand things through that mood. Moods are changing, yet, are a present disposition and need to be acknowledged.

The third term is ‘ground’, or perspective. If our existence is a given (a dasein) yet is contingent, depending on the existence of other things around us, and therefore changeable, then we should also take into account our particularity of that (dis) position and think of the ground or perspective we have in our relation to the things surrounding us. From where do we speak? If we want to see possibilities, if we want to understand things, we should also acknowledge and take into account our ground and our view. This frame of our disposition influences all of our utterances. When do we speak? What do we say? What is there to say and what are the consequences? Is it all contingent, or are there things that are necessary to say? What conditions determine speech or rather open up chances?

1.2 Parrhesia as discussed by Michel Foucault.

In both Le Courage de la Vérité, The Courage of the Truth, and Le gouvernment de soi et des autres II, The government of the Self and of others II, structuralist philosopher Michel Foucault speaks about the Greek term “parrhesia”. Parrhesia is an essential element of speaking the truth about ourselves, and qualifies the other as a necessity in the game of the duty of speaking the truth about ourselves.

Parrhesia can have two different forms, one “saying everything”(unfiltered), the other, speaking the truth unconditionally, without flattery or masquerade of rhetoric (open and honest). Parrhesia cannot happen without taking certain risks, saying your truth can lead to all kinds of different reactions, such as irritation, anger, or feeling hurt. In times of social media and discourses around freedom of speech, this concept is highly relevant to explore and contextualize.

Aristotle, in his Nicomachean Ethics, connected parrhesia to “megalopsychia”, greatness of mind. In a way, rhetoric and parrhesia are completely opposed, what we see in rhetoric is the art of speaking as a form of manipulation and persuasion. Parrhesia is also connected to the place of individuals as citizens, and how they act and behave (ethos). In early forms of ancient democracy parrhesia was a right to fight for. It had its dangers even if it was a privilege right. Parrhesia is also dangerous for both the city-state as well as the individual, since democracy could be undermined.

The goal of parrhesia is rather more the wellbeing or ethos of the individual than that of the city-state. Foucault shows that there is a relation between parrhesia and psychè. And that the aim of parrhesia ultimately is to accomplish mostly changes in the soul and mind. The meaning of the term parrhesia can be transformed and it could be seen as a process which can be beneficial to the city-state, and to individuals, if it is directed to the psychè of individuals and the development of their ethos.

Socrates had the courage to publicize contrary opinions in front of the assembly, and was sentenced to death for challenging the status quo and stimulating critical thinking and disobedience in Athenian youth.

Other forms of parrhesia can be found as well. The understanding that a wise person speaks when it is necessary, when it is urgent, but usually hides in the silence of their own wisdom. Acts can be justified or not, but introspection is important. Exetasis, as Foucault describes, is the exploration of the psychè. The self-research is combined with self-care (epimeleia). Socrates asks Crito the question: Should one take into account the judgment of all others? Should we be taking into account the opinions that people hold? Or should we listen to people who know about that subject?

The didonai logon, self justification, connects ways of being with the self of the psychè. The aesthetics of life (bios) is an historical theme and connects to words, subjects and objects rather than metaphysics.

It is remarkable that Foucault further connects parrhesia to cynicism. The original practice of cynicism is very different to what we currently regard as cynical, but the brutality and freedom of the original cynics, adds to their dismantling ways. The cynics reject useless conventions and want to expose in order to shine light on the subject at hand and show other options.

In our contemporary quest for solutions, it is interesting that exposing convention or injustice is part of how social (counter) discourses are shaped, yet, how little real solutions are found from this exposure?

1.3 What can this discussion of parrhesia mean for ‘The Big Dialogue’?

Participating in a dialogue, or in ‘The Big Dialogue’ takes courage because it means you will expose yourself to ideas and consequences of positions that might challenge your perceptions or habits. Participation has to be mainly verbal; hence there is a crucial role for the use and choice of words. If we see a direct connection between speaking out freely, and telling the truth about yourself during the dialogue, then this courage in itself adds up to self-positioning and self-expression. The parrhesia that can be most relevant and fertile for ‘The Big Dialogue’ is when speaking out contributes to the development of ethos, hopefully, in all participants. If individual expression becomes input for collective reflection, the exchange of ideas can contribute to shifts in our understanding of subjects at hand. If we do not express and exchange, there will be no resonance, hence no intellectual or emotional effects. Our self-care and self-development cannot take place without the addition of other human experiences, in both good or bad forms.

The things we have to speak about matter. We can speak after having had long and deep thoughts, or speak more spontaneously (impulsively). Words come with urgency, and cross the silence. Those are the things that move us. This movement is social, because no words or thoughts exist independently in this contingent world we inhabit. This movement is lyrical because it needs expression and with expression comes shape, form, and effect. But of course, parrhesia is an ideal as well. In real life, in order to be constructive, speech needs an environment that is receptive and not too threatening.

People consider their fellow participants and, in a way, it is a different thing to take into account the opinions of others, and to take into account who we are talking with as part of these environments. Considering that discussions with others does not need to limit our thoughts or our words, we can, for instance, consider the tone of our speech and communicate according to the atmosphere or subject at hand, without censoring our content. This doesn’t necessarily mean we speak rhetorically, but fine-tuning seems unavoidable in reality.

2. Expression (the self, establishing relations)

I spoke so far about contingency and parrhesia. ‘Chances’, ‘moods’ and speaking openly as fundamentals to dialoguing. Not one dialogue we held was ever comparable to another. Every participant adds to a particularity that is unreproducible. Every group dynamic was different, even at times during the same session. Some individuals have a stronger, more articulate or immediate impact on the group than others, yet, that didn’t always mean that they were understood better or their words were accepted more easily.

In a dialogue how to speak is as important or significant as what is being said. A dialogue is not just about sharing content, but also experiencing humanity, difference and sharing experiences, so it is relevant to take this into account, next to the content, what could be relevant for the dynamics of the group and the development of the task and subject at hand. In developing dynamics, elements like enthusiasm, openness, sharing doubts or questions all add to creating responsiveness or engagement in participants. So, even though rhetoric might be opposed to parrhesia, the dynamics of speech and the expressive range in the use of language are things to consider when engaging in a dialogue. Timing for instance is crucial, duration is crucial and knowing when and how to summarize is crucial, and these formal conditions provide a basis for the sharing of content.

Also, it is impossible to arrive at any deeper reflection without taking into account the dynamics. Revelations take time and need the right ‘vibe’. It is something that can happen, but is rarely the consequence of the content of the dialogue, but rather the way that content is accessed or processed.

The clarity of a motif of what to share and why is crucial. The expression often comes from a place of affect rather than intellect. The usage of questions, or questioning can cover up for making a statement. Again, rhetoric slips in.

In an Academy of Arts, of course the how matters, yet the way subjects can be addressed varies enormously. Art is rarely generic. Intention and form go hand in hand. The same counts for ‘The Big Dialogue’. It is surprising that we saw that spontaneity doesn’t necessarily equal openness. There is a truthfulness to speaking, being all in the moment, that writing cannot provide (nor reproduce here sadly). Spontaneity has a promise of liberation, or expansion. And spontaneity is a risk, but there is no creation without it, no joy or enthusiasm without it. Speaking openly doesn’t equal speaking bluntly. Though honesty can, at times, in itself be perceived as being ‘blunt’. Good intentions are important but ‘not enough’, and intentions do not achieve results, nor provide content, hence, intentions have to be transformed. The power of intention is aspirational. A determination to spur action or envision a result, though intentions alone, is no guarantee for good results. During the dialogues we encountered at times a skepticism based on nothing more than its own pessimism. Any ideal already engenders suspicion because of it having an agenda. However noble that intention is, it is not enough.

We often have tried to make ‘The Big Dialogue’ of rather than for everyone in the department. Many participated over the years. Some came once, others came a few times, and a few have joined very often. These differences in participation matter for the effect and perception of ‘The Big Dialogue’. We received comments that ‘Ingrid and Maarten are The Big Dialogue’. We were not, we just tried to do what we could in order to make people talk with each other (not just about each other) and to listen to each other's motivations or ideas in order to create communal understandings. We later learned that some students organized their own dialogues. Perfectly fine, but also interesting to ask why?

So, we have been at all times aware of our role or presence as facilitators, yet we aimed to be participants as well, and show our personality and engagement as if we were also invited to join. This led to questions such as: When do you interrupt the dialogue as a facilitator? How to do this in a non authoritarian way? Especially when often just asking ‘why?’ is an important and effective way to provide the development and continuation of any dialogue.

There might be no definite way of expressing ourselves, but at times, words come across as real or true and those moments are distinct from all others. We can hide words, or choose them carefully, but we cannot hide the impression we make before we even begin to speak. We are very aware to never judge a book by its cover. In engaging in a dialogue we read into each other. We change things by being who we are. The process of individuation, becoming who we are, is maybe never fully finalized. Expression is rarely linear. We need to take into account the connotations, implications and consider possible associations. Maybe, after all, the other is but a different version of ourselves.

2.1 Sharing

Sharing is maybe not the same as collaborating, but in a dialogue, sharing results is a collaborative effort in developing thoughts or options.

So ‘The Big Dialogue’ took place at the Graphic Design department, but also in other departments of different European art schools. We were very aware that these places have all kinds of different bubbles or dispositions. If community building is one of the aims of ‘The Big Dialogue’ then thinking about what kind of community we would like to contribute to, has to be part of the game.

Bubbles can be defined as smaller groupings that are based on affinity and resemblance might be beneficial and safe to the persons included, but we do not learn that much from the things we share or have in common. When being educated or developing ourselves, it is in the challenges, the surprises and sometimes faults we make that we can find new perspectives to fuel our minds and creativity. To dare to be open to this takes courage, not just to speak out truthfully (parrhesia) but to appreciate how we address things matters greatly. Do we have the aim of making the other participants think our way, or do we want to offer the best arguments that are supporting our position? If we do not convince others, we do not change, or refine the challenges at hand. Without this willingness, to listen and to think, we have the tragic conflict between Antigone and Creon (Sophocles).

“But do we reach the ‘right’ people?” One of the participants during a session asked. Hinting at the absence of some people who were said to act in certain ways in class. Participation attended the sessions voluntarily. Implementing aspects of ‘The Big Dialogue’ in classes would be a solution to that. Brainstorming, or exploring concepts could easily be done by applying one of our methods.

Sharing cannot be complete and fragmentation was always part of all the dialogues, and it requires this approach in order to engage and stimulate further exploration and discussions.

When do we know, regarding the issue or subject at hand, that we have enough of the right sources or information to judge or interpret this issue? How do we deal with deviating ideas, opinions, or positions? “If all mankind minus one were of one opinion, and only one were of the contrary opinion, mankind would be no more justified in silencing that one person, than he, if he had the power, would be justified in silencing mankind” John Stuart Mill wrote in On Liberty. Whatever the ideas are, they provide social use, and free exchange is crucial.

Voltaire wrote at the end of his book Candide, “il faut cultiver nos jardins”. We have to cultivate our garden. A sentence urging us to take care of our social environment. Speaking of a garden, it is through attention and care that things can grow or blossom. Improving our own little ‘world’, our ‘garden’, is the best way we can bring on changes, which will in turn bring happiness or satisfaction to human life. Taking responsibility is something concrete and applied. In cultivating, we expand our social (soft) skills. Socialization shapes the brain. Connection is crucial to human formation and development.

3 Connection(through argument, narrative)

In establishing a connection within any group participating in a dialogue, next to the place of rhetoric or speech act, the notions of argument and narrative are also crucial to take into account. Interconnectivity can be helped if arguments are shared and proposed for communal use and not just used for personal motivation, like in a debate where the purpose is winning people over, even though at times this is necessary in a dialogue as well. Humor plays a crucial role as well, though what is considered funny varies and humor has its limits, or can cause division—the opposite of what is wished for. But in general humor can relativize and create breath and respite during dialogues, ‘resetting’ the frame. Interconnectivity in general is helped by making the challenge appeal to as many people involved, by making it ‘theirs’. To make it perfectly clear, we didn’t want these sessions to be educational, we didn’t lecture or present theory, at times we spoke about certain terms, but only when strictly necessary or requested. We tried to create a free space for communal things to happen.

3.1 Interconnectivity by method

When we started ‘The Big Dialogue; initiative, we explored different methods of dialogue to see what we could apply, and what could be useful for sparking conversation and interaction, such as co-design, negotiation etc. Our goal was to start moving mountains to get people to talk and reach interconnectivity.

Any method is in general rather relative when organizing a dialogue, because the most relevant movements often happen aside or after the official frame or goal of the conversation. Yet, a method can contribute to achieving this movement. A method is but a guideline. Some methods ideally ‘fuse’ with the activity they structure, like in the case of the Socratic Talk. The form of this type of dialogue is rather strict compared to others, but it rather helps than suppresses the fruitfulness of the dialogue. In ‘The Big Dialogue’ we focused mainly on the following four methods:

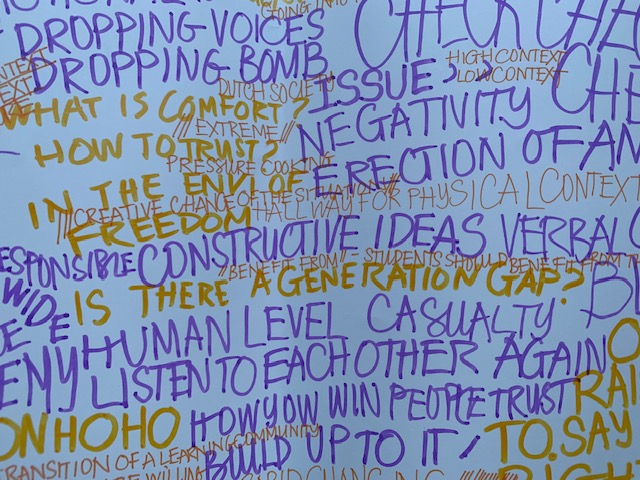

A) Open Conversation/Dialogue: “Bring to the Table”.

With open conversation it is crucial to react, and listen closely for what the potential is of what is being brought to the table. Otherwise the conversation may flow in all directions but not find a focus or articulation. Yet, the place given to chance and mostly to the power of free interaction can be surprising and creative. Since there is no ‘purpose’ other than what is being invested into the conversation, there is less pressure or strain, and this can facilitate openness and playfulness that can lead to sharing and narration. Organically developed conversations seem to gain the trust of all participants most easily. Contingency feels free. We all have ‘worlds’ to enter and discover, we have the hope and promise of not just being stuck in our existential predispositions. Fragmentation, that might be a consequence of this method, is not undermining the potential of depth. Depth of thought, or depth of shared reflection. The “bring to the table” method works as an unofficial inventorisation of what is going on.

B) Dialogue with a specific question

Building up a dialogue through a strategy of relevant explorative, such as philosophical or social questions, has some advantages and disadvantages. Using this method has proven to be very important in explaining the relevance or scope of the question at hand. A thing we didn’t always feel like doing for fear of filling in, or directing the dialogue into a certain direction. Yet, in general, a case study, or example, article, seemed to be effective at times in setting and starting the dialogue, and making the question instrumental and accessible/relatable. In the preparation of these dialogues, it is effective to envision possible outcomes or options to be introduced into the dialogue when certain explorations are starting to loop or get off-focus.

C) Socratic talk

The most constructive, precise, rich, communal, and co-creative method we applied for ‘The Big Dialogue’ (organized during the Philosophy classes in the Graphic Design department, year 3), is called the Socratic talk. A Socratic talk is a structured conversation where a group asks an existential question that requires analysis and thinking. The group questions each other and uses personal experiences in this inquiry process, and thus forms a collaborative investigation that starts from the particular and individual, moving on to a more communal and ‘universal’ perspective in answering the question. The Socratic talk is the most recommended method if unification, inquiry or conflict solving is required.

D) Mixed conversations combining students and teachers, teachers and staff.

During the dialogues, the session we held in Marseille for instance, we had an interesting session questioning our egalitarian guidelines. Can positions be ignored? Can we forget the frame of reality when aspiring to converse on a subject? Who acts as the guide? Can we ever escape our positions of responsibility or ‘power’ during a dialogue? Here there is an explicit danger of hierarchy, conflict, ego and vulnerability.

3.2 Exchange: receiving and giving

Dialogues are exercises in receiving and giving. Soft skills like critical thinking, listening, and exchanging need endless refinement. A dialogue can contribute to this. For some it is easier to give than to receive. We therefore ask, are we willing to receive at all times? And can we always appreciate what we are being given? Rejection, skepticism, frustration, silence, and discomfort, backtracking are just as much part of the dialogues as bonding, laughter, revelations and support.

Some people came to speak, to drop a symbolical, self-expressive ‘bomb’ and leave. Some came to speak and share their viewpoints in order to be understood. Others came to speak and touched the hearts of others. Some participants came to pose questions, or to deny or defy questions. Others just listened. Listening only should not be underestimated because listening is maybe the biggest gift of all. Some people closed down, others opened up. It is all natural and fine.

Conflict or tensions can be uncomfortable and challenging. But also have to exist in order for things to move or grow. A dialogue is not made to confirm but to exchange, which means making space for difference and differentiation. Expressions of disrespect are not acceptable, but when it is a conflict of vision or content, then it is part of the dialogue and a chance for gaining insight. When guiding a dialogue, it helps to focus on the content of what is at stake and not on the person(s) involved. Suggested questions could include: could you explain or elaborate on x or y? An effective dialogue makes space for different arguments and visions, it is not a battlefield. An argument can have a counter argument, but any position has every right to be heard, before it gets explored and questioned. The inner ‘censorship’ will already filter what will be shared and what not, meaning there are possible ideas and arguments that never see the light. What is being said and what is being thought of often differs, so it is important to understand where this thought or comment comes from. Sometimes words are meant to shock, or surprise, but are not to be taken too literally.

Particularities come with any dialogue. Concerning language and the usage of language, Ingrid Grünwald writes about this in her essay, emphasizing that it is very important to neither ignore nor correct such particularities. With personal flairs, introversion, extraversion, associations, experiences and chemistry as examples, it is by experiencing these particularities that we grow our capacity for exchange and interpretation, and we sharpen our senses. This can result in a bigger investment towards other participants and as a consequence, be shaping our empathic capacities. Humans don’t just express, or fear certain things, they reach out to each other, and anticipate exchange. Communication makes life possible and bearable.

3.3 Identification, Empathy

Dialoguing is sharing and creating narratives. Who has the right to speak about what cultural narratives? Ethnicity, history, identity, community often needs to be taken into account. What are narratives that we can identify with? Do we need to identify with something before we can truly understand it, or are we better off keeping some ‘objective’ distance? Do we need to be identical in order to relate or understand certain narratives or histories? Some students made it seem this way. Is empathy enough to cross difference? Can we truly understand any other person at all? We can only try to see things through our own eyes as if we were in that position, and our experiences and our imagination helps us with that. Do we need to speak only from our own experience or can we also speak from our doubts or our admitted ‘not knowing’? When can we address a subject? How far should we legitimize our own view? Or should we at all times be willing to question our own ideas or views? Identification brings people together and separates them from other people at the same time.

Regarding empathy within a dialogue, it has a crucial place, but should not separate participants from each other since everyone deserves empathy. Admittedly with most dialogues there is never enough of a spontaneous (fluid, organic) interaction. Yet, communication and transmission takes place on many layers. By its form, however, dialogue imposes certain expectations and limitations. Participating in a dialogue is an event, it is important to state that there is no clear end result other than where the dialogue might bring everyone, and, at the same time, there is always a reason or motive for a dialogue to take place. It is not necessarily bad that a dialogue seems to restrict or have restrictions at times, because it is also about specification and that is different from a regular, casual, open conversation.

‘Real’ unguarded talk (coming closest to parrhesia) often takes place informally, yet the communication exchanged during a dialogue can often have a stronger impact than anything uttered in a more casual setting.

A dialogue contains descriptions, arguments, examples, narratives, identifications, and moments of affect. There is necessity and space for identification. Identification, as a term, can be found in Aristotelian theories of theater/poetry (The Poetics). The term catharsis, meaning the purification of excess emotions you experience after living into the plot twists of a tragedy (for instance), is a fascinating one. Can a dialogue achieve catharsis too? Maybe, hopefully, but a dialogue is not aesthetics and life is not to be orchestrated into a plot twist like the great tragedies of Sophocles contain. A dialogue remains a co-creation and open. Yet, art often mimics nature and we can be aware of nature through experiencing art and aesthetics and this can help in our thinking of dialogue as a movement and an event.

4 Insight (progress)

Gaining insight is instrumental, and fundamental to education and any social interaction. It is different from acquiring knowledge or developing skills or techniques. Apart from different perspectives and ideas that can trigger and expand individual knowledge, there is also insight in ways of thinking, or human reaction.

Progress in any community can maybe only be made when one dares to face challenges and obstacles and collectively address those, in order to share different possibilities and find collective solutions. A subject viewed by many will result in a richer and sharper contour of the challenges at hand. It is a challenge to make other people’s experiences and narratives partly your ‘own’, but that is what is needed to create changes that are communal, and not just pursue the agenda or benefit of some. This said, people should be granted access to the communal. Oftentimes it seems that certain individuals within excluded communities apply the tactic of counter exclusion, in order to help their process of emancipation. Sub-communities can be crucial for many things, but can division and prolonged disconnection also be seen as a chance? We cannot show empathy or understanding for things we do not know. The fragility or vulnerability of sub-communities needs attention and acknowledgment, but still requires visibility for those outside of the community.

Gaining insight is different from gaining knowledge since insight also takes into account the direction and potential of certain viewpoints. With insight, one can see a way; can gain a vision that is more perceptive, and an understanding that is more accurate. Insight is rather a deeper awareness of our psyche as well as our emotional conditions and capacities.

4.1 Recommendations.

Organizing and participating in ‘The Big Dialogue’ was very interesting. We would encourage everyone to organize and participate in dialogues. We have seen many different developments and dynamics and we have gained hands-on knowledge through the immersive approach we chose. We have been questioned and looked at skeptically. We have seen gratitude and relief, rapprochement and conflict. Personal stories almost always create a special sense of connection. We have heard frustration, seen anger, but also laughter and expansion. At times, the dialogue seemed to really become ‘us all’, but more often, it developed between a few who spoke and the others who listened carefully. What are some of the most emphatic aspects of our sessions that could be helpful in organizing dialogue sessions? See the Toolbox (to be found at the end of this total document) for full input.

- The thinking doesn’t end with the dialogue; it often starts after a dialogue. Intimacy of the setting helps with exchange. The more informal a setting, the easier the flow of the dialogue.

- Organizers of dialogues should not fill in possible silences or awkward moments. Let it exist and find a form of its own. Group dynamics seem formed at these moments as well.

- Take responsibility for the group experience of all participants. A dialogue is not a debate, nor is it about complaining or solely addressing issues. It is a communal exploration.

- Assumptions need to be questioned. Asking ‘why’ is the most important tool during a dialogue.

- If you want participants to take responsibility for community building, they also need to practice and further refine social skills through exchange and verbalization. It is an activity of duration, and endurance, not a fleeting incident.

- Documenting, during the dialogue can be integrated as a method to deepen and connect participants, drawings, models, mind-maps, context, and notes can all contribute. These methods can be chosen intentionally.

No theoretical concept or idea fully dominates chemistry, or mood, like no religion or worldview dominates the unruly power of the Greek Eros. A dialogue is a form of resonance. ‘Being’ is an ungraspable disposition that impacts any attempt to understand it. Yet, our words and actions work upon the world. Concerning a good dialogue, there is not one recipe for success. Everything depends on trust, tone, attention, good will, respect, participation, all of which depends on human chemistry and interest. There is no answer to the reality of our human lives in all of their paradoxes and imperfections. No dogma, ideal or task can ever overcome the unspoken dynamics. Our reflexes, instincts and impulses all play a crucial part in establishing the realities we share and co-construct. We should try to appeal to the reasonable. Next to mood, there is a lot more determining our human existential disposition. We must speak out and have courage. The courage to speak is the courage to be honest. A lot of these experiences can never be put into a simple formula. Despite all of this, connections of inspiration, insight, and amazement can and should happen.

The Socratic talk @ Graphic Design, year 3, 2022/2023

Bibliography

- Aristotle, Nicomachean Ethics. (2019) Hackett Publishing Co, Inc.

- Aristoteles, Poëtica, (2017) Historische Uitgeverij Groningen.

- Butler, J. Frames of War, When is Life Grievable? (2009) (2016) Verso.

- De Heus, G.J. Mastering the art of negotiation. (2017) Bis publishers.

- Foucault, M. Le Courage de la Vérité, (2009) Gallimard/Seuil.

- Foucault, M. Le gouvernement de soi et des autres II, (2009) Gallimard/Seuil.

- Foucault, M. Histoire de la sexualité I, La volonté de savoir, (1976) Éditions Gallimard.

- Heidegger, M. Sein und Zeit, (1927) Max Niemeyer Verlag Tübingen.

- Rorty, R. Contingency, Irony, And Solidarity, (1989). Cambridge University Press.

- Stuart , J. On Liberty, (1859) Parker & Son.

- Voltaire, Candide, (1759) Lambert.

- Zizek, S. Event, (2014) Penguin.

A Manifest to create awareness about the use of the English language in an international Art Academy.

Ingrid Grünwald

3 July 2024

This research is for the tutors and students of the KABK and other European international Art Institutes. It is about the use of language in international art education institutes as I have perceived it in my role as coordinator Graphic Design BA & NLN MA, co-initiator of ‘The Big Dialogues’ and tutor/moderator of the English Clubs in the last 8 years. It is part of The Dialogue as a Research Method within the research group Politics of Knowledge led by Anke Haarman.

In 2015 I started working at the Royal Academy of the Arts (KABK) in the Graphic Design Department. My educational background was English Language & Literature followed by a Free Art Program at the Free University of Amsterdam.

Although my own study period was understandably more or less in English (Scottish English, American English, London Standard English etc. ), I was surprised by the way the English language was the dominant language in an institute where many tutors, staff and management were not trained in this language. What's more, students with a variety of (multiple) nationalities were supposed to understand each other, and more importantly their teachers. Taking part in the Calligraphy class in my first year on the job, I saw students with the same languages drawn to one another. I loved the atmosphere in this class which was more about making than about talking. At the same time, I became aware of the problems in communication by staff, tutors and students alike. During these eight years I organized English classes which became English Clubs (story exchange) and realized together with my colleague, philosopher Maarten Cornel, ‘The Big Dialogues’ in multiple forms (open, Socratic, and performative) at the KABK & in international settings.

In the last 8 years a lot has changed in the language dynamics at the KABK. More and more people became aware of the vulnerability and precariousness of using the English language as the dominant language. Staff and teachers received the opportunity to professionalize in English and through multiple crises the awareness of the different cultural backgrounds of our students and tutor team led to even more awareness. However, although the KABK claims to be a learning community, there is still a lot to be learned in relation to linguistics and the linguistic other in order to communicate from tutor to student, from student to student, from staff member to tutor/student (and vice versa) and from tutor to tutor. Art & Design often operate in places of incertitude and without structure, places of chaos to create and catch something new. In these places “communication” is of the essence.

How can we connect within an international learning community with 61% foreign students when each individual looks through their own lens and has their own point of view ? How can we make something implicitly accessible to a public? How can we make the invisible visible in our communication?

My position is that we all have our own perception of the world. Through language we define our own worlds. However, through my research in theory and practice in the years at the KABK I am certain that we can find each other and connect beyond language.

This manifest is (mainly) written in the dominant English language, because for most of the targeted audience this is the language used in educational institutes and the agreed upon way to communicate. We can therefore look at the English language as the “bridging language”.

Finding Connection by listening

In communication we have speakers and listeners, the message & the context. This is the basic theory of communication. But how the message is delivered (verbally and non-verbally, in which language, in which tone etc.) and how this message is received (emotional, tired, or with a lot of background noise etc.) makes all the difference.

The emphasis in communication is most of the time on the speaker or the sender and we tend to forget how important the listening and reflecting part is in communication. In the previous years, students from the Eastern part of the world taught me about the power of listening. They showed me that the listening part of the conversation was as important as the speaking part. In many conversations they learned to voice their stories and to share their opinions, but I and the other European students learned to listen. In the listening as much as in the speaking we found understanding, together.

In quietness or silence, we can find space to actively listen to each other. When you are in a talk with a group of people who speak different languages, you need time to find your words in your own language and to translate them into a message that is understandable for the receivers. The receiver, however, also needs time to process the message and to translate this into the “home” (heim) language. All in all, we usually have to deal with 2 translations within this dynamic.

As an illustration I added the beautiful poem of Pablo Neruda, Keeping Quiet, in which he asks people to be quiet and silent, in order to understand the world we are living in and to make it a better place.

I agree with Pablo Neruda that instead of stating our opinions and assumptions (the way in which we perceive the world being the better way) we should be more quiet and find out what is really important for us as a person. Are we living the life we want to live? Who do we want to become or to be? How do we want to identify ourselves and what do we not want to identify ourselves with? Especially in our Art Schools, these are the questions our students are dealing with.

Now we will count to twelve

and we will all keep still.

for once on the face of the earth,

let's not speak in any language;

let's stop for a second,

and not move our arms so much.

It would be an exotic moment

without rush, without engines;

we would all be together

in a sudden strangeness.

Fishermen in the cold sea

would not harm whales

and the man gathering salt

would look at his hurt hands.

Those who prepare green wars,

wars with gas, wars with fire,

victories with no survivors,

would put on clean clothes

and walk about with their brothers

in the shade, doing nothing.

What I want should not be confused

with total inactivity.

Life is what it is about;

I want no truck with death.

If we were not so single-minded

about keeping our lives moving,

and for once could do nothing,

perhaps a huge silence

might interrupt this sadness

of never understanding ourselves

and of threatening ourselves with death.

Perhaps the earth can teach us

As when everything seems dead

And later proves to be alive.

Now I'll count up to twelve

and you keep quiet and I will go.

This poem by Pablo Neruda made me wonder why listening and being quiet is so underestimated. The silence in concerts/musical pieces is just as impactful as the music itself, it is part of the whole. Yet it is not considered as such or taken at its merit.

Why is it so difficult in this timeframe to find connection? People in different stages and stations) of their life are struggling for meaning and connection.

How to communicate with each other in a world which is ruled by social media and by talk shows where opposing opinions or judgements are the ‘business model’. A world in constant danger from wars, climate change, right wing nationalistic politics, a polarizing political climate, a generation gap, the increasing influence of AI and biased algorithms.

Religion and spirituality are increasingly becoming less a part of life and education in Western Europe, while in other parts of the world it still remains, or is increasingly important. Religion as a part of identity - like nationalism - and its dogmas as identifiers.

What is still important to us in this world? Where can we find the connection? How can we find ways to understand ourselves and each other and find common ground in this polarized world? This is very difficult for people who speak the same language, let alone for people who speak different languages and are from different parts of the world.

Universities (of Applied Science) in The Netherlands have an established Code of Conduct which also entails respectful communication, as well as a Code of Conduct on the Language used for instruction within the organization.

In the Code of Conduct on Language of Instruction of the University of the Arts The Hague it states:

“We conduct an internal dialogue on the significance of internationalisation for the substance and quality of our education. Practically all of our classes and assessments are conducted in English”

For further reference: Code-of-Conduct-Language-of-Instruction-HdK-def.pdf (2019)

But what is an international educational space? Does this mean an Anglo-Saxon/Western European-orientated ‘colonial’ education with English as the dominant language & ample space for the culture and language of its community? Or are we making use of the diversity of different cultures and languages existing within our art institute?

The new British king Charles in his speech at Mansion House (2023) talks about schooling ourselves and our communities in the importance of our rights but even more of our responsibilities towards one another: “Do we pause, instinctively and unerringly, before speaking or acting to ensure we are affording equal weight to both sides of the balance?”

Angela Merkel (2023) was immaculate in her statement: “Language is the predecessor of action, so when the language takes the wrong turn, action will follow in its footsteps”.

In many of the sessions about intercultural communication I contributed by reading aloud from The Four Agreements by Don Miguel Ruiz, a nagual of Toltec Knowledge:

“Be impeccable with your Words, do not take anything personally, don’t make assumptions and always do your best”. This ancestral knowledge from the Toltecs are great tools for communication. We can find connection beyond language by improving our listening skills and adding time for reflecting upon and processing the world of the (linguistic) other.

Which part of the cancel culture is due to miscommunication?

Cancel culture is a cultural phenomenon which has gained prominence in European Academies over the last years. Students do not feel heard. They have to put up, according to their own opinion, with ‘bad’ behavior from older generations who are higher in the societal or power hierarchy and do not want nor feel the urgency to listen or change. At the same time the world is on fire and in transition, so this young generation feels the urgency for change.

Students do not feel heard like the hippies in the sixties, the women’s protests in the sixties & seventies, the Black Lives Matter marches in 2020. Is this part of miscommunication? Why do they not feel heard? Are older generations really listening and does the younger generation feel that we are in partnership moving forward?

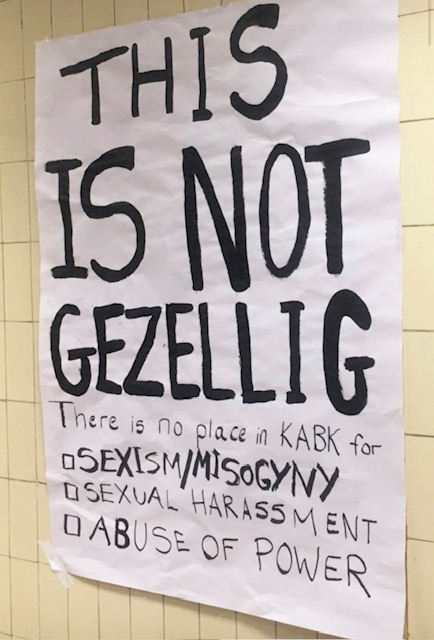

Big Dialogue in Le 75 Brussels (2023) “Cancel culture comes forth from a society (and its “rulers”) where there is a lot of bad behavior towards you, we have to deal with Racism, Sexism, Transphobia, and Homophobia.”

Big Dialogue Beaux Arts de Marseille (2022) “Ici pas de place pour: le racisme,le sexisme, l’homophobie, la transphobie, le validisme”

Big Dialogue KABK (2021) “This is not Gezellig: There is no place in KABK for Sexism/Misogyny,Sexual Harassment, Abuse of Power”

Canceling is a counteraction from a younger generation to an older generation, its government, its hierarchical structures and its way of thinking. It is a countermovement that exposes worldwide, visible injustice from the past due to ‘white colonial structures’, rightwing politics, nationalism etc. : #metoo, #blacklivesmatter.

Although some may think that Art thrives in chaos, uncertainty and total freedom, I observe an increasing demand for structure and boundaries with our students.

Students want to know what they pay for: structure in classes, in schedules, in communication & in expectations. The financial situation of some students may also be adding to the pressure to succeed within the institute, but this wish for structure goes for all students. A number of students also need to adjust to non-hierarchical modes of communication and teaching in their first years. For this the program must be clear from the start, there is little room for improvisation.

In their communication, younger and older generations have to find words, ways to articulate and explain each other’s perspective, each other’s world. It is a worldwide problem. Different generations do not feel at home in the old narrative and are both looking for common narratives that connect. This is not only the case in Art Academies. The Dutch government started a campaign last year concerning the polarization of society and in families throughout generations.

We must find words and time to listen and translate each other’s worlds in order to understand each other. At the same time maybe not everything has to be articulated in words. There can be a place for ‘the unsaid’ to find what is essential for the connection. Connection beyond language.

Finding Meaning in Communication

In Art & Design one can find meaning. The artist can go beyond the ordinary, the visible, and the factual and give meaning.

William Kentridge states that Art has an important polemical and political role … In defining the uncertain. Art should make us aware of constructing meaning instead of receiving information.

Why is it so difficult to suspend our opinions and to listen?

Why is it important in an art institute to seek ways as a community to understand each other and grow?

Why can writers or artists have an influence that lasts your whole life? Where did you find the connection and how are they growing together with you, resonating in your life? And why are they feared by the people who rule?

Artists & writers bring their world to you. You have probably read books in translation. Inevitably these translations alter, however marginally, the content and context. If possible, read these books in the original language, to stay as close to the context and world of the writer. At the same time the appreciation of the book, and of painting, sculpture, and design is in the eye of the beholder and reader. Artists will give a piece of their own world to the reader or the person who perceives the art and who can use and apply this insight to their own knowledge and understanding.

For me these were some writers who showed me new understanding, among others:

- Amy Tan (Chinese American), who taught me about being a minority in the USA and about the use of English, which is judged upon because of its (lack of) structure.

- Louise Erdrich (German Indigenous), who told stories from the perspective of the indigenous inhabitants of the USA.

- Toni Morrison (African American), who gave me insight into the collective consciousness of Afro-American people being enslaved. Being physically free is something totally different than being psychologically free. Her book ‘Beloved’ totally explains, already in 1987, why the #theblacklivesmatter- movement is so necessary.

- Marisa Condé (Carribean French) who writes about the African diaspora and the inner power of being a human despite the circumstances one grows up in.

All these writers/artists constructed meaning in their artworks with words. Artists/writers are creators who want to communicate their perception of the world to the beholder to bring beauty, insight, consolation, happiness, awareness etc. - everything which makes us human.

Closed and Open Networks

But how do we make use of our canons, our knowledge of the world, and how does this work in different parts of the world?

Another thing to keep in mind is the difference between the oral and written tradition of storytelling. The oral tradition is an open system, there is no plagiarism. The storytellers, the bards, the troubadours, the naguals, the griots will give their own version of the story. Think of the many versions of the Spider Anansi in Africa and the African diaspora in the Caribbean and Suriname. In a written canon there is the possibility of plagiarism. But what is plagiarism? Plagiarism originates from the word plagium (Latin) which means kidnapping— the emphasis on the stealing of words and ideas. But isn’t it true that writers are also influenced and inspired by the literature written before them? In our current times we are also encountering stories made by AI. More and more stories and translations of books alike are machine-originated. Moreover, the boundaries between translations written by humans or machines are fading.

But what is the common policy in the Academy. Should we also look for other views within our networks to constitute where our boundaries lie?

Mohammed Mbougar Sarr (The youngest winner of the French Prix Concours 2021) made this so clear in the ‘La plus secrète mémoire des hommes’. The main character is looking for an African writer who wrote down one story and treated this as if it was part of the African open system of storytelling. In the closed West European system this writer was charged with plagiarism and retreated from public life.

What is the linguistic profile of our students that is the portal to their identity/frame of thinking and the tool to find common ground?

People speak roughly 7,000 languages worldwide. Although there is a lot in common among languages, each one is unique, both in its structure and in the way it reflects the culture of the people who speak it. Next to this there are increasingly more people growing up bilingual or multilingual who express themselves in multiple languages.

The KABK-community is bilingual but from experience I would say that two-third of our students and tutors are multilingual. Which leads to the questions: how are our cultural backgrounds defined? Through which lens do we see the world? What is the most natural form of communication to us? Which values are important? And how do they relate to the values of the country/institute you are studying or working in?

At the KABK and in other international communities one encounters many shades of English both in structure and in dialect. We assume that students in an international group listen to each other without emotions, that there is time to really listen and time to ask for verification whether you understood correctly and that there is time to process what has been said. We also assume that there is time for misinterpreted words to be repeated at a slower pace, that we understand someone’s point of departure in a talk.

Understanding different cultural backgrounds, experiences or identities is not something the institute provides. Learning to do this in a respectful way towards the other does not speak for itself. Working and studying in an international Art School in these last few years has been really challenging.

The Royal Academy of the Arts was an ‘international’ school in the making when I started working as a coordinator. The English language was the lingua franca, all classes were taught in English. But at the same time the institute was run mainly by Dutch employees. Learning the English language did not come easy to everyone, a lot of communication was “lost in translation” .

What do we expect from the linguistic ‘other’ in our community?

When you acknowledge that the English language has one of the highest amount of words in its vocabulary, that the British culture is totally different from the American, the Caribbean, and the Australian etc. you understand that speaking a second (or third/fourth) language does not immediately mean that you understand one another.

Upon starting my work at the KABK this was one of my big considerations. How can we teach and make a community in our institute when we do not understand each other. At the KABK we have 61 nationalities. In classes I saw groups of students talking in the same mother tongue, I saw students totally confused at what was happening in the classes. Not only the language but also the culture of teaching was new for many.

Especially for Asian students, taught to be quiet and respectful toward the teacher, a period of adjustment was required to adapt to the nonhierarchical way of interacting with their tutor. Hierarchical structures are changing, behavioral rules are changing because of #metoo, conspiracy theories, #blacklivesmatter, wars in Ukraine and the Middle East.

Amy Tan tries to explain the bias she encountered when she uses her Mother’s English. Her use of broken language being perceived as broken ways of thinking.

“Typically, one language - that of the person who is doing the comparing – is used as the standard, the benchmark for a logical form of expression. And so the other language is in danger of being judged by comparison deficient or superfluous, simplistic or unnecessarily complex, melodious or cacophonous.” (The Opposite of Fate, p286)

But what do we all know about each other? Students from all over the world come together in a classroom and start a four-year program together. They are young, they have passed their admission, they had to take care of a lot of red tape and financial administration in a ‘new; country ' to reach this point.

For some this is a first time in Europe, for some it was easier coming from an international school, for nearly all it is intimidating.

There is also a difference in educational background: we have students who already have received a Bachelor in their home country, students coming straight from HAVO and MBO, students who have traveled a lot already, students who have done the prep year and are feeling more grounded.

During the first 4 years I learned a lot from the students in my English Clubs. I asked the participants what they wanted to learn and made a program around their answers. The programme was not as concentrated on grammar and phonetics but more on conversation and sharing and explaining – giving them a safe place to talk. It is a learning community where topics are addressed that students do not dare to address in class. A place where we find common ground by sharing essential stories that were shared by all. I guess we tried to understand each other as well as ourselves.

In 2019 Covid changed the world, and we had 2 years of minimal personal contact. Students from all over the world had to be in The Hague, with just a few classes together in the building, and no places to hang out and find each other. One of the most special and engaging English Clubs originated during this time – a Club of students finding each other in the exchange of language and culture. We exchanged narratives, we exchanged expressions and cultural similarities and differences. We exchanged food and (personal) stories. We found connections.

Use of your own language

In literature writing in one’s own native language brings strength. For Zora Neale Hurston, a black writer in the first half of the 20th century, it was liberating to write in the language she spoke and grew up with instead of the language of the ‘white’ oppressors. She did not have to leave her community to write about her community.

Nora Zeale Hurston was a role model for black writers who followed in her footsteps like Alice Walker, Maya Angelou, Audrey Lorde and Bell Hooks.

As Audrey Lorde later stated: “You cannot dismantle the master’s house with the master’s tools”.

If this is also true in Art Education, language and the way to express yourself is of the utmost importance. In Anglo Saxon and French education, culture voicing interaction in the classroom is a more integral part of the students' development than in the Dutch system. If there are 61 nationalities at the KABK with different backgrounds (some of them have more than 1 nationality or cultural background) the dialogue and conversation should be an integral part of the curriculum. The use of language and the construction of meaning should be tools in art education for the tutor and student alike.

In the booklet of Bonaventure Soh Bejeng Ndikung ‘Pidginization as a curational method – messing with language and praxes of curating’, he teaches us about the effects of a dominant language in all cells of life.

He talks about creolization (adaptation), marronage (separation), indigenization (liberation) *Sylvia Winter, “Black Metamorphosis”: New natives in the world.

Pidginization is, in his opinion, a way of being in the world, a mode de vivre, a lingua franca. But because of its free structure, it was seen in a colonized world as a language for kids, illiterates and the mentally deficient; Pidgin was deemed a language of the primitive, lazy and corrupt. Seen in the same way as the English communication-skills of the mother of Amy Tan.

When I was younger, I also perceived the pidgin language and maybe even the language of Zora Neale Hurston and creole languages like Papiamentu as childlike because it was not the ‘proper’ use of the ‘English’ language nor of the ‘Spanish’ language in the case of Papiamentu. But at the same time I am a big fan of the music of Fela Kuti, because although you cannot understand all that he sings, you do understand what he means. He constructs meaning.

Ndikung explains: “There are probably more people around the world who speak some form of Pidgin and live some form of pidginization culture than those who speak the supposedly dominant colonist languages of English, French, Spanish. German.” (Pidginization as a Curational Method p.43)

If you are aware of these phenomena, why not give more space to students to work and express themselves in their own free ‘speech and living’ space.

Experiment with languages as a tool for expression. It might help in dialogue to find more understanding. If the privileged student with an international baccalaureate speaks the dominant English language better than the teacher, why can’t you try to find a place for pidginization? Within Art Education we teach our students to question the status quo, to think critically and to experiment. Is the use of language not part of this attitude we ask from tutors and students?

In Audrey Lorde’s When I dare to be powerful (1984) she shows us the importance of language in order to speak out to survive and grow. Although she speaks about her own community, from and for her own community, her message is universal.

So, if you are not making “proper” use of the English language or if you speak with a heavy accent, does this make you an unreliable narrator?

The use of Language and Context

“The ability to observe without evaluating is the highest form of intelligence?”

J. Krishnamarti

The context in which one speaks, and writes is as important as the communication. This is the reason why pure communication from one person to another is so difficult.

The books of Willa Cather, with so many beautiful descriptions of the life of the first pioneers in the Midwest of America tell us just one side of the story of the land. It does not tell us anything about the indigenous people who lived in the Midwest and were driven away or destroyed. We read about the courage of the pioneers not about the downfall of the indigenous people.

But the same goes for the novels of Louise Erdrich who tells her family story from the perspective of the indigenous people and gives voice to the traumas and racism they must put up with. To know the whole story, you must be able to critically search and find different voices in history.

For me Edward Said’s autobiography opened my eyes. Not only because of his many identities, being a Palestine with a US passport, being an Arab and a Christian, having a British first name yoked to an Arabic Surname.

In his autobiography he tells us that the worlds he lived in across different periods of his life are disappearing. Thinking about all the worlds he lost, I realized this goes for every person in a small or bigger way. Worlds disappear and you are not the same person as years ago.

When you return to your home country after 4 years KABK, will this be a return to what you were used to? Both the context and you, as a person living in this context, will be in constant flux. Worlds disappear all the time. My colleague in the department of Typography, Thomas Buxo, explained to a candidate for admission that we have to reinvent education every day because education is not static, and is connected to the changing universe surrounding this curriculum. Everything is in flux, including the language.

We not only want to exchange information, but we also want to construct meaning. We want to teach students to be critical thinkers and have the skills to make this world a better place.

Why is language such an important vehicle in finding connection?

Answering the question I asked the English Club participants: could you find through communication sufficient connection in your group, the students answered: no.

The students lack connection outside their own group. This has to do with culture, identity, and different ways of communicating. A Chinese student gives the example of greeting a person, this is done in such a different way in China, in Korea the different ways to greet people depends on, for example, age. You will never say I love you or send a heart to your peers on social media, in Korea or China. These were customs they had to get used to. In year one the pressure was also so high that there was no time to interact and engage.

The language and cultural barriers were huge, the administration they had to deal with was horrific. Eating food together was comforting. It was so much easier to connect to Asian students because of their collective memories. They missed jokes made in class because they did not understand.

The different perspectives of students about limitations were mind-blowing. These Asian students stated: “we love limitations and someone telling you what to do” whereas European students know best themselves.

Finding common ground

To create space for exchange and connection has always been the essence of ‘The Big Dialogues’ in each setting. The same goes for the talks in the Graphic Design and Textile departments.

Can we speak out freely and find a common ground to connect and understand each other’s worlds and ourselves a little bit more, especially in polarizing times.

Are we using the same terms – does this term mean the same for you? Try to find the meaning & origin behind terms, try to feel the term – how can it be used? Is it a negative word or a positive word, a cynical or heartwarming word, what is the story behind an expression – it will tell you so much about the culture.

What does a word like radical mean? It has different meanings in different languages.

Use the right words and know what they mean, try as a student and a tutor to expand your vocabulary and try to get a feeling for language. With room for correction and for humor. Humor is also culturally ingrained, how can we find a safe space to share our jokes, our irony etc.