Tatjana Macić

what you are holding in your hands now is an assemblage in an assemblage, a multiplicity of assemblages emerging from heterogeneity of my artistic practice…

The idea that assemblage might be something I should investigate further, came to me while I made installations for my exhibition Leftovers. Taking a meta-view of my artistic practice and positioning it in the broader context is like trying to use my hands to pat my head and rub my belly simultaneously - what a joy and disarray! I engage in such multitasking exercises both reluctantly and excitedly. Reluctantly, because I crave to make and long to keep the process of making opaque, circumspect, maybe even magical. Excitedly, because I am a curious being and my pleasure principle is rooted in discovery and the production of knowledge. Combining these two attitudes and processes is a particular effort and a profound shift for me. In alignment with this twofold investigation, whilst taking my exhibition Leftovers as the departing point for this research, I aim:

- To reflect upon processes in my intuitive artistic practice and situate myself in the broader context by using theoretical and auto-ethnographic methods of investigation. This essay is one of the modes of reflection and dissemination of my research in the framework of a publication by this research group. Other ways being researching literature and sources, exhibition-making and engaging in conversations with peers in the research group. I will investigate assemblage as a research method in the framework of exhibition-making. Is it purely an intuitive process or can it be cognitively understood, expanded and mapped in the context of my practice? What methods, knowledge production and principles are underpinned by the assemblage and exhibition-making?

- To make new assemblage-based work that is informed by my research for the Politics of Knowledge research group at The Royal Academy of Art The Hague.

For the purpose of this investigation, I intend to focus on the philosophical, spatial and artistic propositions connected to the idea of assemblage. I am interested in bringing together objects, languages, spaces, histories, nostalgia and artistic processes in the context of exhibition-making. For this reason, I will look into the assemblage in the Deleuzian sense, as articulated by Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari in their collaborative work A Thousand Plateaus. I consider the Actor-Network Theory (ANT) to be of less significance for my research at this point because it focuses on assemblage as a social and not an artistic process. ANT was introduced in the 1980s by Bruno Latour, Michel Callon and others, where assemblage is proposed in the context of social theory by introducing non-human actors and positioning them on the same level as human actors (Latour, 1988). Over the years, concerns have been expressed by scholars (Atkinson) that ANT lacks clear vocabulary (Latour, 2005), that it is a form of flat ontology and that ascribing agency to material entities could lead to fetishising them or obscuring the underlying structures of dominant production (Vandenberghe).

The origin of the word that I find so enchanting, assemblage, comes from Middle French to “assembler”, to bring together. The verb that flows from it, to assemble, does not abundantly signify underlying multiplicity, therefore, I prefer to use a self-made verb, assemblage-ing. As proposed by Deleuze and Guattari, the idea of an assemblage revolves around the possibility of dynamic configurations of un-fixed heterogeneous elements that come together because “the assemblages are in constant variation, are themselves constantly subject to transformations” (Deleuze and Guattari 95). The assemblage is underpinned by the concept of rhizome and relates therefore to the rhizomatic principles of connection and heterogeneity, multiplicity, asignifying rupture, cartography and decalcomania. Those principles are not operating in an isolated manner, and are addressed when applicable (Deleuze and Guattari 5-12). In particular, I will look into heterogeneity and asignifying rupture in the context of the emergence of assemblage because I have observed that these principles align well with my processes. The book, or publication, is taken by Deleuze and Guattari as an example of an assemblage and described as “neither object nor subject; it is made of variously formed matters, and very different dates and speeds” (Deleuze and Guattari 2). Assemblage is therefore not a static structure but rather a fluid and evolving network of relationships between various entities including people, objects, ideas, institutions, histories and more, that are assembled together albeit temporarily to produce new assemblages. As such, assemblages are seen as sites of potentiality and transformation, where new forms, meanings, and possibilities can emerge through connection and disconnection. This does not imply that Deleuze and Guattari provide a well-organized and academic framework to work with. Au contraire. If there is anything they provide for it is complete chaos, ambiguity and unaccountability on their part, which is appealing and frustrating in equal measure to me because this terrible attitude suits my artistic process surprisingly well and allows me to add, subtract, multiply and transform at will.

A sense of urgency

The persistent commercialisation, mass-production and institutionalisation of the art scene, as we have seen recently at the Venice Biennale and Documenta, along with cuts in public funding on local and global levels, have reduced spaces for artists to engage in experimentation and critical discourse. How could the art world become more sustainable and resilient?

To counter-point these disastrous politics, W139, an artist-run space in Amsterdam since 1979, which takes a special place in the Dutch art scene by championing risk-taking artistic processes (NRC, Verhoef and Soudagar), invited artists, designers, curators, mediators, local initiatives and communities to show projects and ideas they consider urgent and relevant in September and October 2023 in the exhibition W139 Hosts… The Leftovers exhibition was amongst 40 or so initiatives out of 450 that responded to an open call to be selected by W139. Every week 5 to 7 exhibitions, events and performances were shown to the public. The Leftovers was hosted in the last week of October, which presented me with the possibility of collecting materials from other exhibitions. Assemblage could offer a holistic approach to sustainability and exhibition-making. In my own artistic practice, language, ecology and spirituality play important roles, and whilst these interests are in a state of flux, lately they converge towards topics of sustainability or rather circular production versus capitalist commodification and collectivity versus individuality.

By tracing my process for the Leftovers exhibition and by investigating assemblage theory and adjacent theories, I have identified underpinning principles and research methods that arise from my exhibition-making practice. Henceforth I will outline these principles.

Departure principle: urgent sustainability and ecology

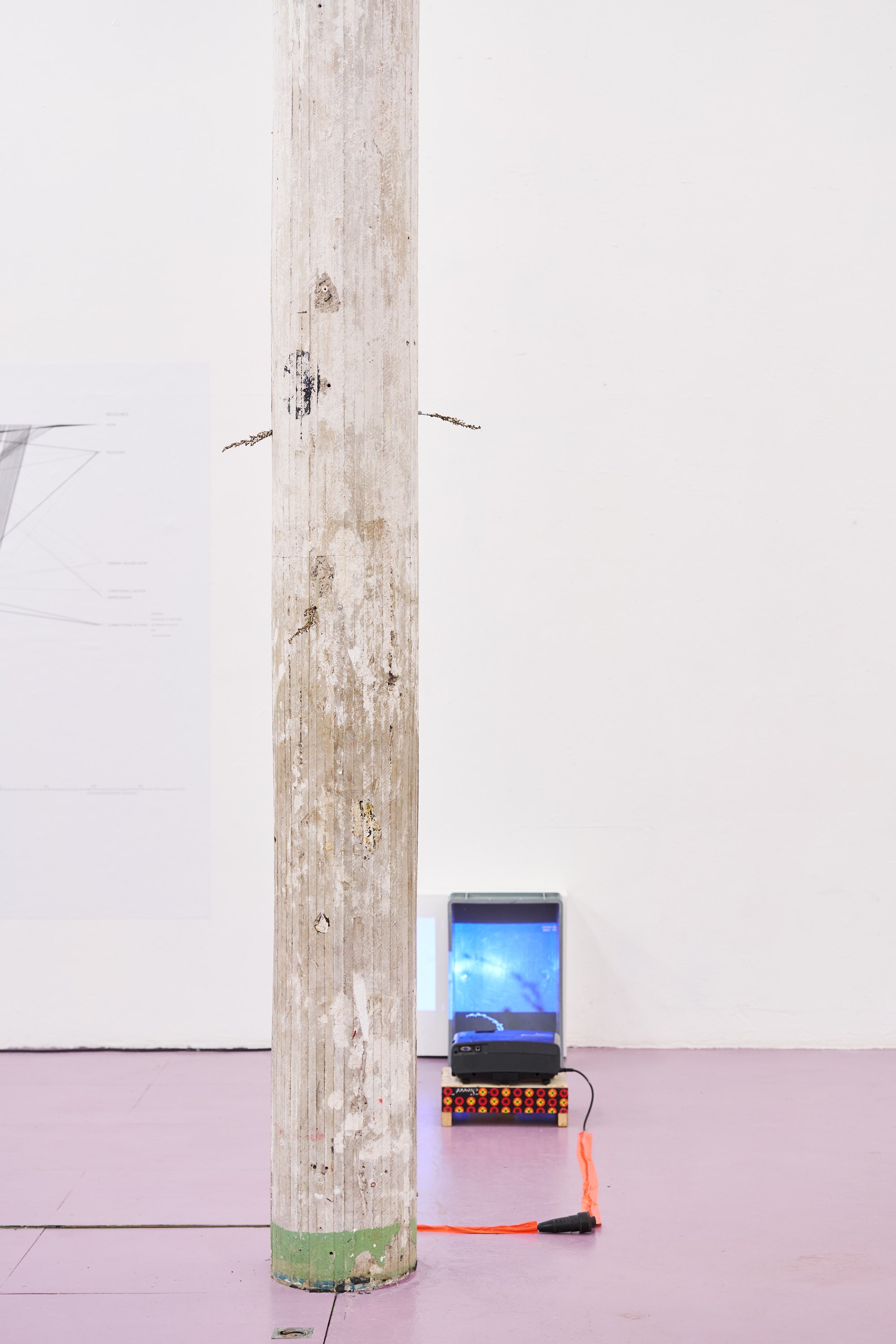

The Leftovers exhibition consists of installations, sculptures, spatial interventions, notations and video projections I made by using only the discarded materials from other exhibitions in the framework of the group exhibition W139 Hosts (images Nr. 1 - 13). The notion of reusing or recycling is not new in art, nevertheless, it is an urgent issue for us today, given the pressuring ecological, social and existential threats we face on this planet. By only using the leftovers or the discarded materials, I choose not to engage in the mass production and commodification of the art world.

Growing up in Eastern Europe has taught me to reuse and recycle all resources at my disposal; and that my wish to collect discarded materials and basically trash from others comes from the desire not to waste Gaia’s flesh and abundance. The word ‘sustainable’ or ‘sustainability’ points to the use of resources in terms of the survival of the subject and the environment and often is object-centered, as Object-Oriented Ontology proposes. Classifying the world into the human and non-human categories is such a binary and patriarchal approach. One could consider approaching the world in a more holistic way since all forms of life are connected in a vast, entangling mesh (Morton). In this sense, the question arises if assemblage could offer a holistic approach to the sustainability issue we are currently facing. In relation to the Deleuzian notion that a book is not an object or a subject that has astonishing similarities to Kristeva’s notions of abjection (Kristeva, 1982), I would like to argue that the collected objects could be understood as abjected in Kristeva’s sense: abject is not an object or a subject because it once was a subject, it is “a jettisoned object” that is “radically excluded” and draws us towards a space where meaning collapses (Kristeva 2). The single-use objects in capitalist production and mass consumption are creating ‘jettisoned’ objects on a mass scale. Repurposing or re-using such objects gives them new life and context, and provides space for critical production and collaboration.

Throwing a wide net: collecting, archiving and conversing

I collected materials for new artworks in Leftovers by asking artists, collectives, communities and curators who took part in the W139 Hosts… group exhibition to lend or donate materials that they will not use any more after they deinstall their exhibition. Discarding something can be interpreted as a rapture that accelerates the heterogeneity and diversity of the collection or a temporary assemblage (Deleuze and Guattari, 2). The prospect of coming into the possession of something new and unpredictable every week ignited a feverish state in me. What will I get, a pile of hair, a wrinkled piece of cloth, a used wooden beam… or a tin of food? Dealing with the unpredictability of collecting became the first phase of artistic production, a rather satisfying activity and an unruly passion. For me, collecting is a necessary process, a way of throwing a broad net, like fishermen at sea do, to catch whatever is there. To feel with my tentacles what lies ahead, or as Donna Haraway puts it: “the tentacular are also nets and networks, it critters, in and out of clouds” (Haraway). My net was an exhibition and the catch at the same time.

Conversation: an ephemeral and precarious method

During my collecting phase, something happened that I did not fully anticipate: a form of deterritorialisation (Deleuze and Guattari, 166) by language, namely by conversation. What role could conversation and the knowledge that is embedded in conversations play in the further making of the assemblage that follows later on? Can conversations evolve into a node from which new rhizomes and potentially (components of the) assemblages can spring? As I entered into conversations with exhibiting artists and curators, a discourse emerged on the fringes of the exhibition-making, this can be interpreted as a form of soft deterritorialization of social strata. Spoken and written language is of particular significance for my practice, for example, I write poetry, micro operas and short stories. Also, language and text form constitute an important part of my visual work. Often I am faced with the decision to choose one primary language from three languages I speak daily, Dutch, English and Serbo-Croatian, choosing thereby an underlying historical, political or cultural context of that language.

Assemblage-ing as a method allows me to cross-pollinate languages, images and objects. Conversations which took place with artists and curators became an important ephemeral material I was collecting, a production of knowledge and community forming. However, it is useful to note that one perhaps cannot expect to find a solid art community at W139, even if such an ideal is sublimely needed (Zizek), rather, one can interpret it as an assemblage, an assembly or a heterogeneous network where pollination between the elements is possible. DeLanda takes the following definition of assemblage as a starting point for his outlook on the assemblage and assembly theory: ‘It is a multiplicity which is made up of many heterogeneous terms and which establishes liaisons, relations between them, across ages, sexes and reigns – different natures. Thus, the assemblage’s only unity is that of a co-functioning: it is a symbiosis, a ‘sympathy’. It is never filiations which are important, but alliances, alloys; these are not successions, lines of descent, but contagions, epidemics, the wind’ (DeLanda). After several conversations, I became aware that W139 might be a form of the social assemblage with agents or components with temporary affiliations (Ibid 2). This would make W139 a very agile and yet precarious social assemblage. However, if the art scene or network is made of too many precarious assemblages, in totality it might be susceptible to dismantlement (as we have witnessed by the governmental budget cuts), because the affiliations do not offer enough stability or durability since they offer temporary social cohesion. It might be useful for the art scene in the Netherlands to look into itself from the position of the precarious social assemblage, not just as a network of institutions.

Viscosity: a quality of non-materiality

A deeper understanding and a sense of kinship became an essential part of these conversations. The ephemeral multiplicity of words, memories, and sounds… formed precious ‘material’ that I was to work with, that held a meaningful yet fleeting quality. In which way could ephemeral parts of the assemblage: a quality of non-materiality that often appears in my artistic process and that I map and transcribe into a memory and/or humour - become a part of a larger assemblage? I chose not to document conversations formally but to entrust them to my memory and to listen more. Listening to others is a soft skill and necessity we could benefit from more (Hanula 44-59). Having a conversation is often not just a method to extract information, rather it is a way to connect to others, to hear one’s voice and the voices of others, to capture the unspoken, the unheard and the nostalgic. It is the fleetingness of human-to-human exchange that is so appealing to me, the limited temporality of short connection, to be held and experienced for a moment. To let the ephemeral be ephemeral and let the ephemeral remain nostalgic. I interpret this as a viscosity of the assemblage, a term Deleuze mentions several times without further explanation.

The principle of viscosity can be observed when a subjective, singular, vernacular, local and authentic experience of an individual taps into the universal yet evenly lived social flow of plurality, to be sublimated into a shared and accessible site or a social imaginary. Forging thereby a shared narrative that binds everything together in both clear and unspoken, implied ways.

Archiving: an abject, feverish investigation

Collecting has led me to storing and archiving discarded materials at W139. A precarious, narrow wooden staircase that leads into the dusty basement, the institutional underbelly- quickly became my trusted space for storing and archiving the growing pile of discarded stuff: my archival womb and cave, which will cradle me during the exhibition, only to reject me at the finissage. The fact that many artists could not provide information about when and where they purchased those materials proved to be a challenge for simply processing and identifying the objects, their origin and meaning. One day in the dusty basement, an object appeared in my imagination. A sphere or a tumbler with signs on it, turning and revealing the archive to the observer in a fluid manner, much like the clay cylinders inscribed with descriptions of objects in three languages made by the Babylonian princess Ennigaldi-Nanna, considered today to be the first exhibition-maker and museum founder in the contemporary sense. Archiving heterogeneous materials and objects by keeping lists and logbooks, thereby fixing the meanings in an academic way, proved to be counterproductive in terms of the artistic processes. By entrusting the information to my memory, I became the living archive of exhibition-making. Such a process is similar to how writers operate, keeping an archive in memory banks, with compartments ready to be consulted just by the power of thought (Murakami).

Slowly, the archiving frenzy transformed into a sense of being overwhelmed, a feeling described as an archive fever (Derrida). Sorting through the stuff, being surrounded by the physical presence of objects that once were commodities and which will possibly undergo a political and ontological transformation ignited the archive fever in me which I can best describe as a deeper sense of nostalgia, abjection and an archival impulse, “an idiosyncratic probing into particular figures, objects, and events in modern art, philosophy and history” (Foster).

The feeling frequently came over my body as a wave and lifted my thoughts as an undercurrent. I felt like an explorer, a shaman and a ghost, an archon of the assemblage.

From the archiving process a certain jouissance in the Lacanian sense arises “as in jouissance where the object of desire, known as object A [in Lacan's terminology], bursts with the shattered mirror where the ego gives up its image to contemplate itself in the Other, there is nothing either objective or objectal to the abject (…). Obviously, I am only like someone else: mimetic logic of the advent of the ego, objects, and signs. But when I seek (myself), lose (myself), or experience jouissance—then ‘I’ is heterogeneous. Discomfort, unease, dizziness stemming from an ambiguity that, through the violence of a revolt against, demarcates a space out of which signs and objects arise” (Kristeva 10).

Reflecting upon the exhibition space as a large rhizomatic networking site or a body, at one moment it appeared to me as a body without organs in terms of the consistency of a plane and how the plane has sections with multiplicities of variable dimensions (Deleuze and Guattari 589-590). An archive without an event is not functional.

The principle of archiving is twofold: it is an embodied experience of an explorer, an archon troubled by the archive fever which needs to be evoked, and it is a deeper sense and act of ontological transformation of matter, histories and shared viscosity of the ephemeral quality, that beckons to be re-imagined and to provide an entry point to the public, to the eventful and the eventful knowledge.

Auto-ethnographic method(s)

Know thyself, as the oracles of Apollo have spurred us to do, is probably a reason I create, thou, how can I/one know oneself without knowing the world? How can one know oneself without doing?

By tracing my steps and methods, by this and other writing, analytically and emotionally recalling the events, drawing, noting, conversing, and self-reflection, I am connecting my personal experiences with a broader cultural and social context (Carolyn) and representing my research in evocative ways. Such examples are my drawings of a fold by using a handkerchief that belonged to my late father, and collecting. There is a deeper meaning to collecting leftovers or casting a wide net, and it relates to my so-called migrant background. Being displaced since the age of a young adult has provided me with a state of undercurrent flux, a sense of permanent travel and nostalgia, even when I am stationary. Being a migrant has its tragic sides, a displaced human is one without organic social tissue, nothing can replace what is lost, for example, family, childhood friends or places that we cherish that do not exist any more or continue to exist and evolve without us. Displacement demands survival skills, flexibility, and adaptiveness to inner and outer situations and forges a new agency: an agency of displacement.

Constructed in Pseudo-Greek in the 17th century, by assembling to return home (νόστος, nóstos) and longing (ἄλγος, álgos)- nostalgia might signify a longing for a place that was or never was, the real and imaginary sense of home and belonging. Or, nostalgia can be interpreted as an entanglement of the local and universal histories (Boym). The need to collect, to cast a wide net, comes from the deepest wish to understand what is around me, to identify it, probe it, sift through it and hold it even for a brief moment. To establish a connection to the world ahead - since what remains behind is unstable, "connecting thereby radically any point of what is found to anything else, in a rhizomatic fashion” (Deleuze and Guattari 5-7). Nostalgia is a form of antagonism and pondering- a much-needed weight or gravity in the otherwise optimistically oriented assemblage theory by Deleuze and Guattari (Zizek).

Auto-ethnographic methods are guided by an underlying sense of nostalgia and collection of leftovers and have led to my discovery of the agency of displacement.

Language-ing

Next to my practice as a visual artist, I write poetry, short stories, novels, and critical texts in three languages: Dutch, English and Serbo-Croatian (my mother tongue). I am often faced with the decision to choose one primary language and thereby an underlying historical, political or cultural context of that language.

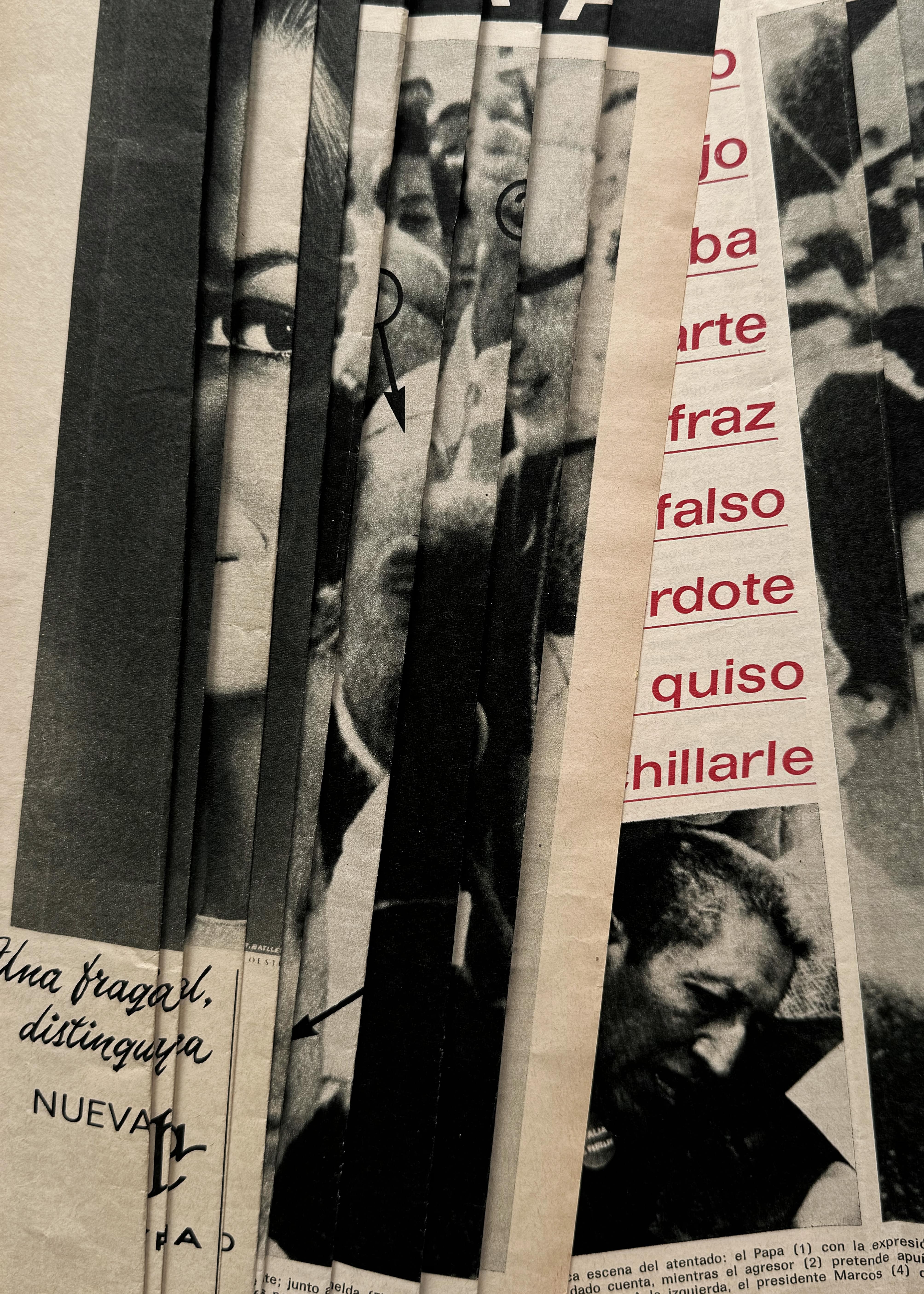

This multilingual approach transforms into installations, in writing and voicing or performative language. In Leftovers, in installations, language was made transparent, as a visual, and physical experience. It consists of two types: conversations and found language or found texts, prints, and notations in leftover materials. Language became a vehicle for revealing multiplicities and underlying connections between found objects and a way for ‘collective vocalisation’ through conversations I conducted. Language appears not only as an embodied means of communication, it presents as a symbolic order, and as a means to distinguish between elementary registers of the symbolic, the imaginary and the Real (Lacan 1977). Cross-pollination of these registers, symbolic orders, memories, images, sounds and ways of communicating results in a cross-pollinating principle of languages I named language-ing. It manifested in leftovers and my other works in the forms of murmurs, whispers, micro-operas, writing, noting, collaging…

Balancing out three different languages with three registers, and three symbolic orders has become a principle when the cross-pollination of meanings appears.

a giant nebulous glow

in the corner

in front

in front

behind the mountain

outntain

nema

moze

cekaj cekaj cekaj cekaj jecaj

wolg glow

Hiding and showing

The exhibition space is presumed to be the space for showing, and exhibiting to the public (Duncan). In certain measures that is what happens and that is what it simply is. However, showing implies hiding and vice versa.

By throwing a wide net, I have collected discarded wood, nails, foam, candy, props, kitchen utensils, duct tape, plants, bingo cards, plastic bottles, books and more. The obvious versatility of the collected matter while making the installations invited me to think about the heterogeneity of the proposed order of things. A temporary network in which some things are prominent whilst others are hidden or neglected, some are in the forefront and visible to the public, whilst others are in the background or obscured from the viewer, both in the physical sense and in a political sense of accessibility of knowledge. If something is hidden it is desired. It embodies the qualities of a desired object —object petit a— a sublime quality that drives us to desire it even more (Lacan). The object petit a therefore is a leftover that embodies the lack of subject and the presence of the desire. The assemblage and by extent the whole exhibition, is not just a tangible object/space that can be possessed, but rather objet petit a: a fantastical construct that escapes capture and drives the desire of the maker, the audience and the observer, by constantly shifting and changing form, thus maintaining the subject in a state of perpetual pursuit of hiding and showing, and realisation that it should recognise itself (Lacan 270).

The principle of hiding and showing is deeply connected to the assemblage in terms of potentiality for transformation, for new forms, meanings, and possibilities to emerge through the process of connection and disconnection. It is a site for power-plays and powerlessness, for political and anthropological, for the sensory and the senselessness, for lacking and desire. Whilst showing seemingly offers access to the public to engage with the artworks, the hiding entices the public to search, discover and choose their paths of exploration, the dynamics of showing and hiding perpetuate the desire and situate the exhibition space as a site of intrigue.

Pressure points

In the Leftovers exhibition, I have taken up the position of an exhibition-maker, or an agency of an artist and a curator in a shared or conjoined authorship role, or a meta-author (Bishop) to engage in exhibition-making, therefore I do not speak of curating as an agency, an institutional position or a particular cultural role here. I approached the exhibition space as a part of the assemblage and started to identify spots on walls, the columns, the floor and elsewhere in the space, where I could situate installations. These pressure points are areas of particular sensitivity that signify a possible rupture of the rhizome. Identifying pressure points, where the rhizome is shattered, or ruptured in contact with the Real (exhibition-space) and where a new line of rhizome appears, asks for a particular skill of allowing for the possibility of a spatial and temporal appearance of the assemblage. After identifying pressure points in the exhibition space, I aligned installations on these points. The intricate heterogeneity of the assemblage manifested itself: the old wood beams assembled and connected to the dried plants, liquids connected to the plastic bottles, kitchen utensils to the sponges, sponges to the mdf bits touching the walls, foam embracing the mdf bits, nails going through the plaster, paper cups touching words… These spots exist when more lines of the rhizome intertwine, in the diagonal lines of the assemblages: the lines that are between things, between points, that break and twist and form nomadic and anomalous multiplicities (Deleuze and Guattari 587-588).

The effects of asignifying ruptures in the exhibition space and within installation works, are catalysts of change, allowing for the emergence of connections that mark the formation of (temporary) deviation from the pre-established order, demarcating new rhizomatic relations within the heterogeneous assemblage. Thereby, the assemblage in my practice operates on the axes in opposite directions: it territorializes and deterritorializes the strata, and it is the heterogeneous quality that allows for such complex action.

The principle of pressure points allows for the emergence of ruptures in the Real and the actual exhibition space, in contact with the meta-author. The exhibition needs the exhibition-maker and the real and discursive space to be activated or performed. Pressure points offer an understanding of practical engagement with the installation of art in physical, political, historical and social space.

The fold

In this process, I came to recognise the fold as a principle of assemblage that involves rhizomatic lines and pressure points in space that relate to each other by two types of folds: soft and hard fold. Once I started to think about folding, I realised that humans have practiced folding since the dawn of time and that it is a way of dealing with our surroundings as well as a biological necessity. For example, when we fold plant leaves to eat them, the way we fold paper planes (hard fold) and croissants (soft fold), folding our clothes in cupboards which are made with the idea of keeping folded items in them, we fold paper in newspapers, in books and posters, we fold our arms in front of us when we are observing or when we are taking a protective posture, we fold and unfold our tongue many times a day when speaking, eating or just for fun, we fold glass, concrete and steel to make buildings, we fold and unfold umbrellas. There are many types of folds I am investigating, to name a few: the valley fold, mountain fold, accordion fold, Z-fold, blintz fold, book fold, gate fold, tri-fold, reverse fold, squash fold, pleat fold, box pleat fold, Miura-fold; these are all essential folding techniques implemented in origami, packaging, textiles, mathematics, science, astrophysics, spacecraft and engineering. Two types of folding can be recognised from all these types: soft and hard fold.

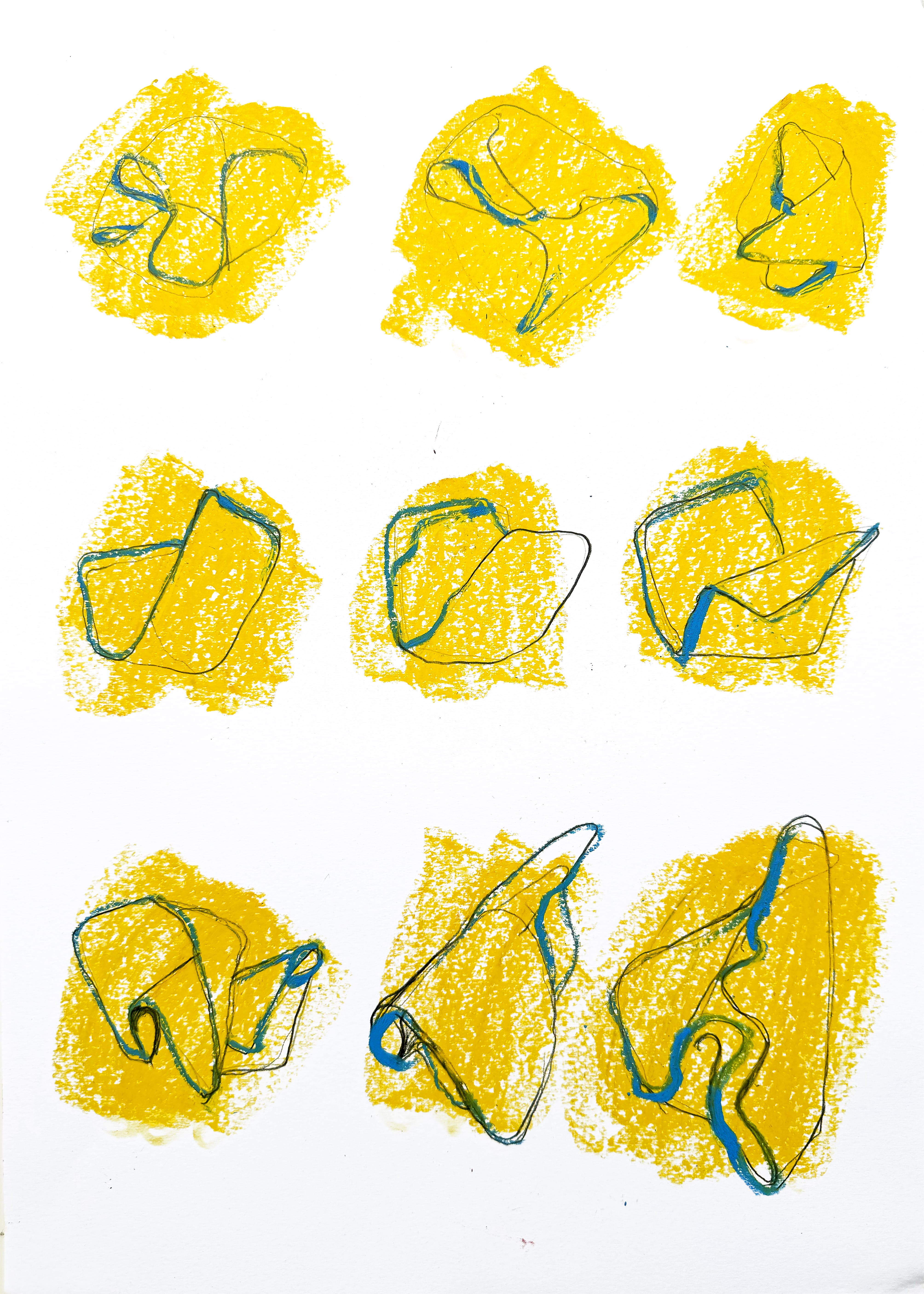

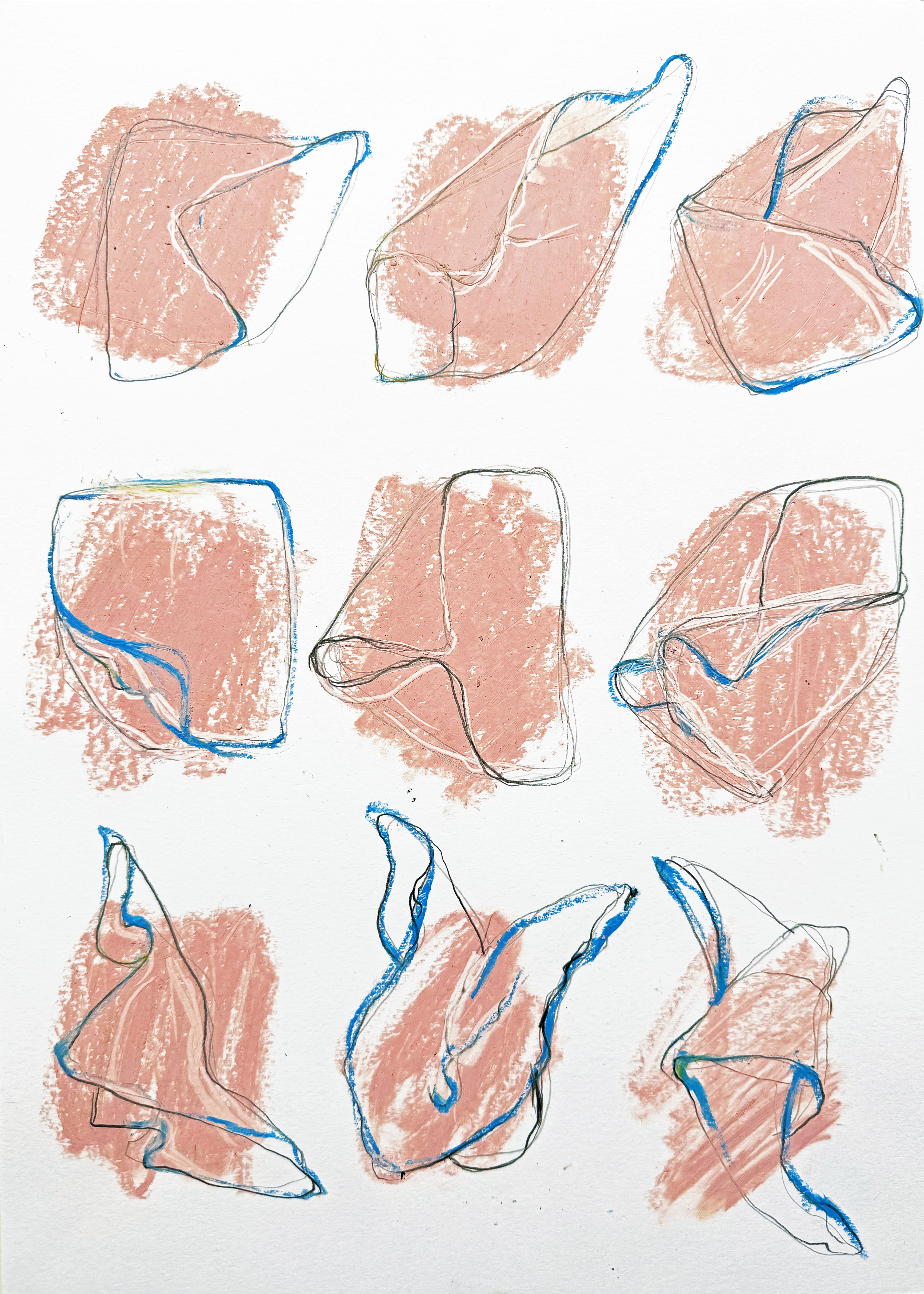

Soft folding refers to the fluid, organic, continuous, and dynamic transformations that characterise natural processes and living organisms. Soft folds are an organic, flexible approach to understanding change and development pertaining to the seamless, infinite foldings that occur within the fabric of existence, where each fold is interconnected and perpetually evolving. Such folds can be found, for example, in baroque architecture where forms are in a state of constant metamorphosis (Deleuze 1993). The soft fold can be seen in the pastel drawings and sketches that I made using a handkerchief of my late father (images Nr.14 and 15). I drop the handkerchief from approximately a meter high from the drawing surface, and let it fall on it, allowing for the chance- folding of the soft, light blue cotton-based fabric. Each time the handkerchief falls, it creates a different soft fold. This allows for the bending, curving, and organic shaping of the material. Drawing in soft pastel mimics the softness of the handkerchief, providing for the unity of matter, drawing and hand gestures.

Hard folding involves a defined, more rigid and segmented approach to folding. Such folding highlights the abrupt transitions and distinct demarcations within a system or a space, representing a more static, vectoral, architectural and mechanical form of transformation. For me, this type of fold is prominent within the social, political, non-human and cultural context because the shift and separations are more abrupt compared to the soft fold. The raptures are more geometrical, like in a sketch for the work that I made from my archive of the Western European newspapers from the 1950s and 1960s. The lines are vector-like, sharp, the bending of the paper is rigid and does not allow for much change once the line and the direction starts the crease of the paper, forming thereby a pleat fold. The hard (un)fold can also be seen in Leftovers in the installation with wooden beams and the actual folding of papers (image Nr. 16).

Furthermore, the fold also refers to cultural and political connotations, such as ‘being in the fold’, being included or excluded from certain social groups, it also refers to the opposite action of folding, unfolding narratives for example, and all other actions that include folding usually are followed or preceded by some types of unfolding.

The fold as the principle of assemblage-ing relates to and signifies change, flow and transformation in organic, fluid (soft fold) or social and geometrical sense (hard fold).

Magical Labour

The awareness behind Leftovers and some of my other works, and exhibition-making in a broader sense is a way to respond to performativity, commodification and dissemination of artistic labour, leisure and languages that emerge during the production of exhibition-making. I consider the production of works of art and exhibitions in a neoliberal context and propose new modes of production that consider such labor to be unquantifiable. Such labour is an amalgam of labour in the Marxist sense and of singular, authentic production that is unique to each exhibition. Magic in this sense vaguely relates to the deus ex machina of the Greek theater, alchemical processes, folkloristic miracles, mythology and magical thinking.

The principle of magical labour is an activity unique to the artistic agency and exhibition-making of the assemblage. What happens when all leftovers are collected and when installation art is about to be made? It is a moment when all underlying here-above described principles of the assemblage come together in unity and without hesitation.

To conclude

Assemblage-ing, as a research method, offers a powerful tool for investigating and articulating the processes of artistic practice and exhibition-making. It provides for the accessibility and connecting of the works of art to the public in various forms. It allows me to manifest as the meta-author, to operate as a maker in space, and to be critical, discursive, nostalgic, playful and analytical.

By focusing on the relational and processual nature of artistic and exhibition practices and methods, assemblage allows me to move beyond reductive and linear modes of analysis, embracing instead the interplay between the complexity, singularity, the spatial, languages and the social imaginary. In the course of this investigation, I have identified underpinning principles and research methods that arise from my exhibition-making practice and assemblage to be: Departure principle: urgent sustainability and ecology, Recycling, Throwing a wide net: Collecting, Conversing, Archiving, Viscosity: a quality of non-materiality, Pressure points, Hiding and showing, Language-ing, The fold (soft and hard folding), Auto-ethnographic method(s) and Magical Labour.

My research has led me to a better understanding of the underlying processes and implications of exhibition-making relating to my artistic practice and to the broader field of artistic research. I consider this investigation to be just one of the initial steps towards future research and the process of assemblage-ing.

Literature

- Atkinson, Will. "Field Theory and Assemblage Theory: Toward a Constructive Dialogue." Theory, Culture and Society, vol. 41, issue 1.

- Bishop, Claire. “What is a Curator?- essay presented at Shifting Practice, Shifting Roles: Artists' Installations and the Museum”. Tate Modern, March 2007.

- Boym, Svetlana. The Future of Nostalgia. Basic Books, 2002.

- DeLanda, Manuel. Assemblage Theory, Edinborough University Press, 2016

- Deleuze, Gilles. The Fold: Leibniz and the Baroque. Translated by Tom Conley, University of Minnesota Press, 1993. Continuum, 2003.

- Deleuze, Gilles, and Félix Guattari. A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia. Translated by Brian Massumi, University of Minnesota Press, 1987. Originally published as Mille Plateaux, volume 2 of Capitalisme et Schizophrenie, Les Editions de Minuit, Paris, 1982. Paperback edition by Bloomsbury Academic, 2020, 3rd print.

- Deleuze, Parnet, in: ”Dialogues”: The Folds of Post-Identity”, The Journal of the Midwest Modern Language Association, Vol. 36, No. 1, Thinking Post-Identity (Spring, 2003), pp. 25-37.

- Derrida, Jacques. Archive Fever: A Freudian Impression. Translated by Eric Prenowitz, Edited by Mark C. Taylor. University of Chicago Press, 1996.

- “Doe jezelf dat plezier, ga kijken, en verrijk je”: de beste exposities van 2022, NRC, 13 December 2022.

- Duncan, Carol. Civilizing rituals:inside public art museums. Routlege, 1995.

- Ellis, Carolyn. The Ethnographic I: A Methodological Novel about Autoethnography. AltaMira Press, 2004.

- Foster, Hal. An Archival Impulse, Octotber 110, MIT Press, 2004. pp. 3-22.

- Haraway, Donna J. “Tentacular Thinking: Anthropocene, Capitalocene, Chthulucene.” e-flux Journal, vol. 75, Sep. 2016.

- Kristeva, Julia. Powers of Horror: An Essay on Abjection. Columbia University Press, 1982.

- Lacan, Jacques. Écrits: A Selection. Trans. Alan Sheridan. London: Tavistock Publications, 1977.

- Lacan, Jacques, Seminar XI: The Four Fundamental Concepts of Psychoanalysis, ed. Jacques-Alain Miller, trans. Alan Sheridan. 1998.

- Latour, Bruno. "Mixing Humans and Non Humans Together: The Sociology of a Door-closer." Social Problems, 1988.

- Latour, Bruno, Reassembling the Social. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005.

- Murikami, Haruki. Novelist as a vocation. Penguin Random House UK, 2024.

- Muestenberger, Werner. Collecting: An Unruly Passion: Psychological Perspectives. Princeton University Press, 1995.

- Morton, Timothy, The Ecological Thought. Harvard University Press. 2010.

- Vandenberghe, F. "Reconstructing Humants: A Humanist Critique of Actant-Network Theory." Sage Journals, vol. 19, issue 5-6.

- Verhoef, Gijs, and Roxane Soudagar. “Onrust in Amsterdamse kunstsector na advies over subsidies: ‘Waar is dit een oplossing voor?’”, Het Parool, 19 July 2023.

- Zizek, Slavoj. “Totality or Assemblage”, lecture 1, 2 and 3. YouTube last visited on 4 May 2024.

Biography

Tatjana Macić (she/her) is a visual artist and writer who merges visual art, exhibition-making, and language. Her origins in a now non-existent country profoundly influence her work. Tatjana's alchemical creative process results in lecture performances, found-object installations, artistic archives, interventions, collages, poetry and digital art. Her work has been exhibited at W139, Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam, Venice Biennale Collateral Events, The Wrong Biennale, KunstVlaai, and de Appel in Amsterdam. Tatjana holds a BA in Fine Art from ArtEZ University of the Arts and an MA in Theory and History of Contemporary Art from the University of Amsterdam. She lectures at the Royal Academy of Art The Hague.

poster

poster 01

01 02

02 03

03 04

04 05

05 06

06 07

07 08

08 09

09 10

10 11

11 12

12 13

13 14

14 15

15 16

16

Politics of Knowledge (2022–24), Lectorate Art Theory & Practice at the Royal Academy of Arts.