Sophie Allerding

- I once lived on the back of a sea monster, constantly uncertain about our survival atop the unfathomable beast. I began to understand how we might kill what gave us ground to be alive.

- I was once a bat in the forest, and when humans built their city further into my habitat, I lost my bearings and tried to smash up their city in a blind rage. In the end, I only lost myself.

- I spent the last night before the fall of patriarchy with my sisters. While we drank the tea of thousands, we realized how silent the world would become.

In times of great uncertainty, humans tend to grasp all forms of knowledge production to find answers, to know. Such times lead us to turn to forms of knowledge production like future predictions, prophecies, and divination. The most famous in Western intellectual heritage is probably the Oracle of Delphi. The Oracle of Delphi was a role taken by a priestess, the Pythia, in the temple of Apollo, the god of prophecies. Despite knowing the answer to everything, no prior knowledge or education was required to become a Pythia; a young, virgin woman was chosen. Prepared through procedures and by priests, she would enter a trance to answer the questions of the enquirer.[4] The Oracle's answers were often cryptic, a riddle to be solved by the questioner. The meaning of the message emerged between her mouth and the ears of the inquirer, through their subsequent enactment as embodied interpretation. What happens in the question and answer game between the Oracle and the questioner is, to me, collaborative storytelling: the Oracle's words only gain meaning through the questioner's interpretation and action. The questioner's actions are prompted by the prophecy, and their actions are in constant relation and reflection to the prophecy.

The Oracle was always right; if its prophecy did not come true, it was the inquirer who failed to solve the riddle. Many stories emphasize this message, such as the famous one where the oracle declared that "no man is wiser than Socrates." Socrates, aware of the limitations of his knowledge, did not believe the oracle and set out to find someone wiser than himself. He determined that anyone who knew what was truly worthwhile in life would be the wisest. He began asking everyone about it, but the more people he spoke with, the more he realized that no one seemed to have a good answer. Instead, they pretended to know something they clearly did not. Finally, he recognized the truth in the Oracle's answer: he was the only one admitting that he did not know it all and recognizing the limitations of his knowledge. This humble realization was what made him the wisest of all. Perhaps it is not fair to credit Socrates alone for his wisdom, as his realization was a collaborative production with the Oracle.

Embodied storytelling through LARP

LARP, an acronym for live-action role-play, is a form of participatory media, collaborative world-building, or a simulation model of a temporary society. Participants assume the roles of characters within a fictional scenario, creating and enacting stories together. While the LARP scenario and characters are fully fictional, the emotions experienced within it are real, as are the interactions between players. In a LARP, I temporarily lend my body to another character, feeling what my character feels, thinking how my character would think, and acting as my character would act. This helps break through usual thought patterns and provides a way of being in and knowing the world from another perspective. Nevertheless, all my actions in character are informed by my own experiences, so I am not claiming to know the world as a different character but relating to its position through my own. Through LARP, I gain knowledge about another position not through facts but through empathy. LARP helps us understand our own limits of knowing and thus brings awareness of the many other ways of being and knowing the world. In that sense, LARP is a practice that cultivates a sense of a plurality of knowledge.

While LARP shares similarities with performance and theater—such as character portrayal and narrative immersion—it differs fundamentally in its lack of a traditional audience. Instead, LARP features a so-called first-person audience, a term defined by Christopher Sandberg which describes the phenomenon of playing and watching play simultaneously. Instead of a secondary identification with, for instance, a protagonist that is followed through an already created fiction, in LARP, the fiction is created and inhabited by every participant, each of them being the protagonist in the same story because they experience it in a first-person narration. A first-person audience in a LARP does not mean that there isn't a shared audience. On the contrary, it is mainly the collective effort that makes the story and depends on both collective connection and commitment to the fiction.[5]

Just as the role of the audience changes, so does that of the author in a LARP, as her task is not to tell the story but to create a framework in which stories can be told, a magic circle[6]. The term magic circle is nowadays understood by the definition of game scholars Salen and Zimmerman for whom the magic circle is “the idea of a special place in time and space created by a game”[7]. The magic circle is a defined space that differs from ordinary life and in which especially the rules of everyday life are suspended and exchanged through the rules in a game. It is a social contract between players on how to act together in a contained space. As Nordic LARP designer Eirik Fatland states: “When we design LARPs, we play with the building blocks of culture... But asking people to act As If is not enough to make a LARP. As LARPers we need to act As If together... This is what we do, as LARP designers, which is to describe and communicate the minimum requirements needed to direct human creativity towards a shared purpose[8]. The role of a LARP designer is to create a fiction and dynamics in which collaborative and embodied storytelling can emerge, while keeping the balance of not presenting a much too defined story to give players enough room to create, at the same time giving enough ground from which a collaborative story can grow. A LARP is only complete when it is played, without players there is no LARP and without the framework there is no ground on which to play.

LARPing and knowledge production

It is undeniable that play functions universally as a form of knowledge production: young beings, human and non-human, come into the world and learn how to navigate their way through play. Play and knowledge production are deeply intertwined as asking questions and solving riddles marks the birth of philosophy and the motor of scientific knowledge production. In his seminal book Homo Ludens the author Johan Huizinga discusses the importance of play as a primary formative element in human culture. In his chapter Playing and knowing he traces back the riddle-game as one of the oldest forms of philosophy and knowledge production which has its origins primarily in the spiritual realm and ritualistic formwhere people consult a higher power and receive messages and prophecies through it, explaining the unknowable. He writes: “the poet-priest is continually knocking at the door of the Unknowable, closed to him as to us. All we can say of these venerable texts is that in them we are witnessing the birth of philosophy, not in vain play but in sacred play. Highest wisdom is practiced as an esoteric tour deforce. We may note in passing that the cosmogonic question as to how the world came about is one of the prime pre-occupations of the human mind.”[9]

In a way I find LARPing on many levels similar to oracling: Like the Pythia my body becomes a vessel through which I channel thoughts, emotions, through which I act out messages in another world. The collaborative act of oracling already happens between me as a player and me as a character, sharing one body. My hands and my mouth, my actions and my words become the manifestation of this character in the real world and inside of myself. As a player I ask the question and as a character I react upon it. In a first-person audience position I observe my own play, making meaning out of it, often filled with a sense of wonder or surprise about the outcomes, as I was not aware that I could access this form of being and knowing the world through a character. Furthermore, I see the storyweaving between the players as oracling, each of them bringing their own thread and collectively weaving narratives into the unknown. Lastly, as a LARP designer myself, I also encounter on this level the question-answer, word and action game that takes place between oracle and interviewee: I give the intentions on which action is taken and from which the story is formed.

What LARP offers through the possibility of embodying a fictional character can be compared to other forms of knowledge production that work with different embodiments, such as historical re-enactments or psychodrama. Psychodrama, developed by Jacob L. Moreno and Zerka Toeman Moreno in the early 20th century, used guided drama and role-playing to work through problems. Similarly, in historical re-enactments, participants take on the roles of historical figures to better understand historical events through embodied experience. Through LARP, psychodrama, and historical re-enactments, participants can step into different perspectives and gain insights that would be difficult to access otherwise. This practice of stepping into different perspectives can help foster empathy and understanding, broadening our sense of what is possible and imaginable.

The three paragraphs at the beginning of this essay are my attempt to formulate a LARP experience into the knowledge it has brought me. I note down the role I have taken and the position I have related to and one of many conclusions I have drawn from this experience. In the second example, I look at the game Spillover, designed by the artist and LARP designer Alex Brown. In this LARP, players alternate between playing bats and humans, with humans not representing individuals but rather nations, both richer and poorer. The game deals with the spillover process, where, for instance, a pathogen crosses from one species to another. In this example, the pathogen jumps from bats to humans as humans encroach upon the bats' habitat, creating contact that makes spillover possible. The game was non-verbal, with humans able to express themselves using all vowels, while bats had their eyes covered and could only communicate with high-pitched "I" sounds. This led to the bats' habitat on the game field being threatened and encroached upon both spatially and sonically. Practically speaking, one could say that I learned about the spillover process through the game, not in theory but in practice, as I caused the process myself- as a human, I was busy competing with other humans to occupy space. As a bat, I felt my habitat shrinking and, additionally, the increasing noise made me lose my orientation. This led to direct contact with humans. The game can be seen as a sociological model that allows for the analysis of the dynamics of greed and competition and how these lead to ruthlessness, selfishness, and loss of empathy. From a psychological perspective, one could say I learned what it feels like to be displaced to the point of powerlessness. I played the game in January 2023 at the Black Box LARP festival in Copenhagen, and it was designed with the emerging COVID-19 pandemic in mind, which resulted from such a spillover. The game also served as a reflection on the interdependency between human health and environmental destruction.

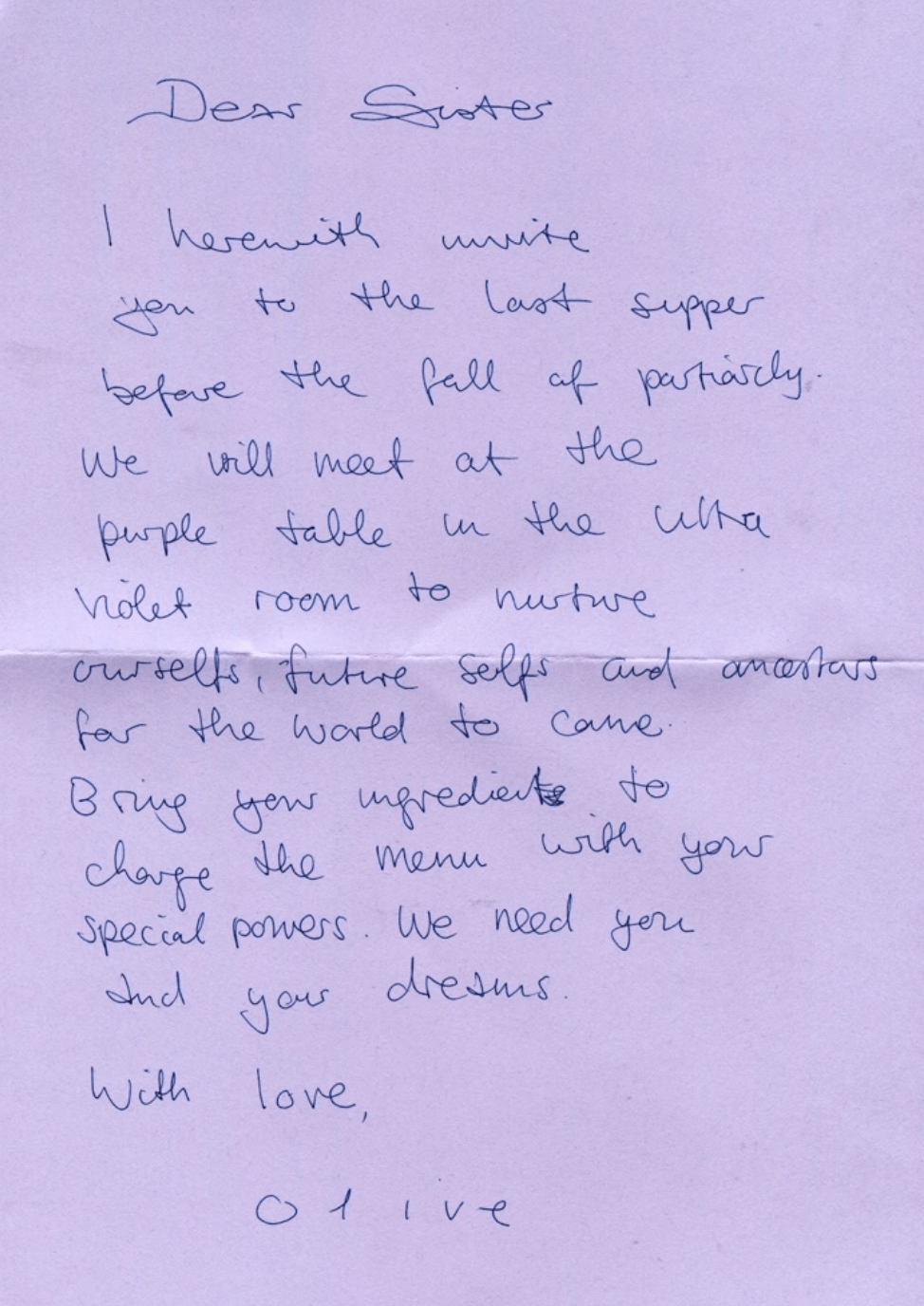

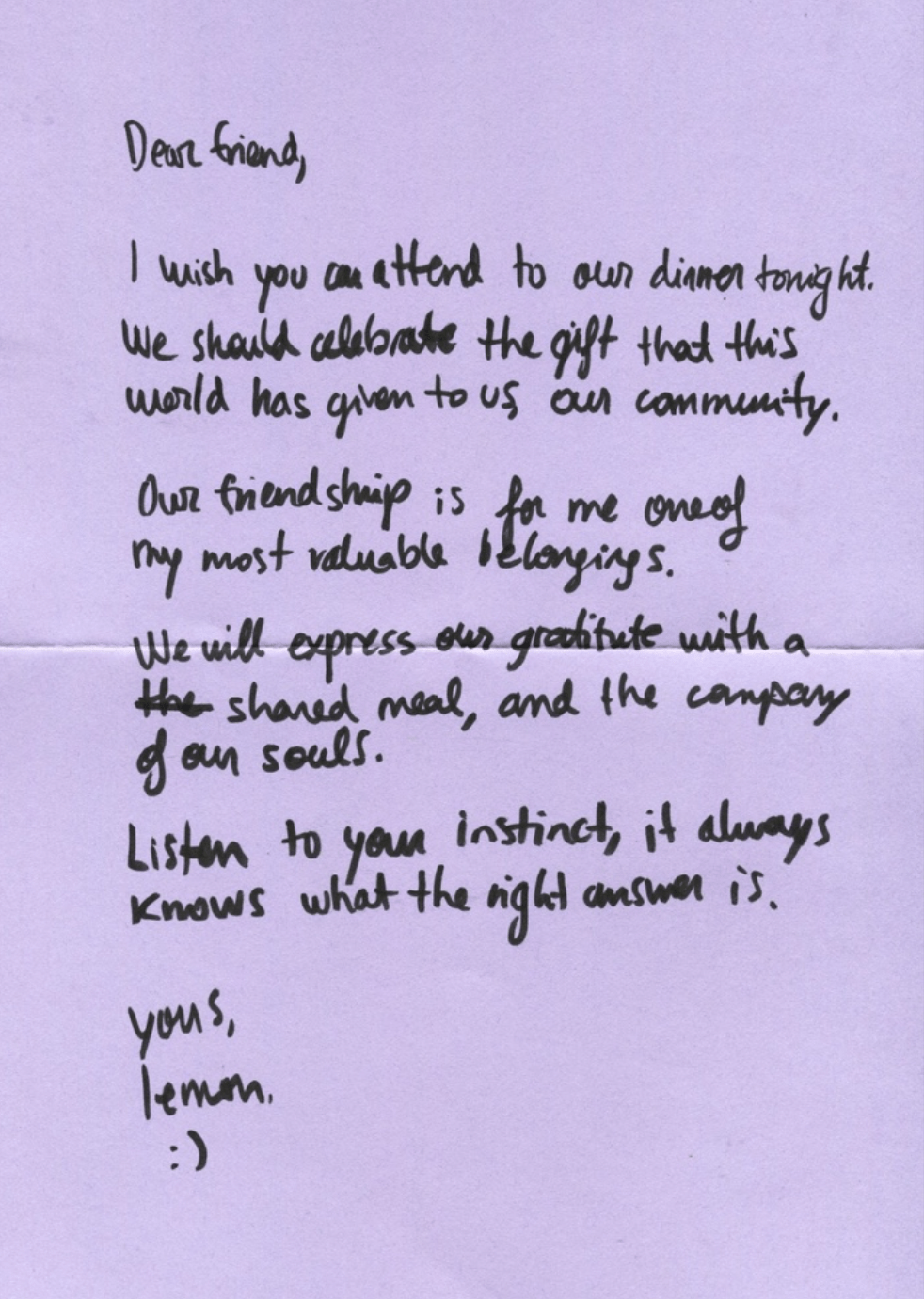

Invitations, created inside the LARP Ultra Violet, May 2024

I like to use LARP as a tool to learn about what the future could look like. Because LARP frees us from the constraints of our everyday life persona, we might start imagining a situation different inside a game, such as a specific future or past. The new ideas which spring from us in another state, inside the fictional framework of the game, are nevertheless knowledge about what we could imagine to happen in the future. Imagination is crucial for action. Only when we can imagine a world different from ours can we take steps towards creating it. Hence this new knowledge can be impactful and useful outside the fictional framework and the magic circle of the game. So LARPing can actually become oracling.

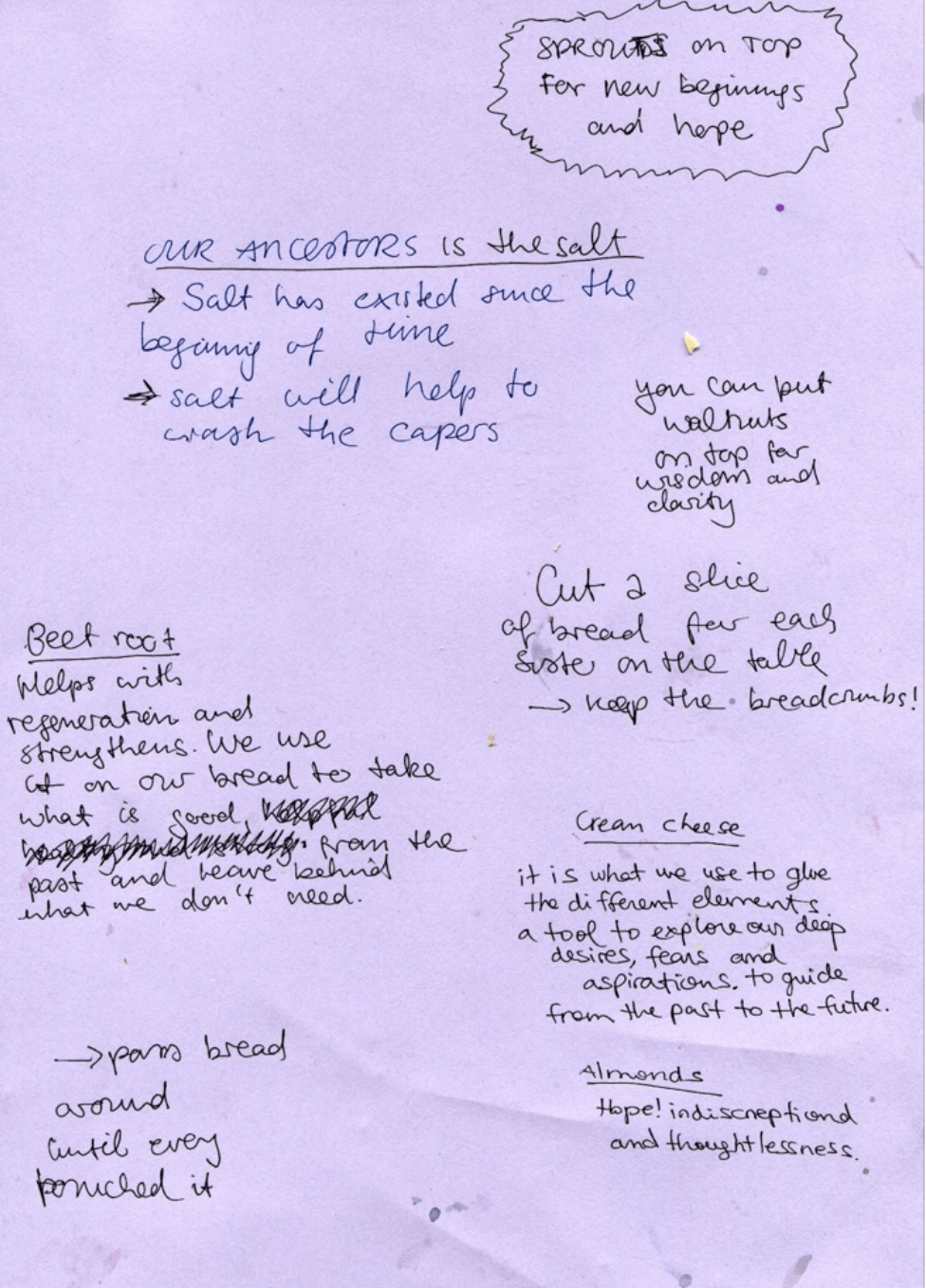

In the LARP scenario Ultra Violet we wanted players to imagine what a world after the fall of patriarchy would look like. The game emerged out of a collaboration with artist Lucila Pacheco Dehne who examines the relationship between food and resistance in the form of creating menus/manifestos. The goal of the LARP is to explore the connections of cooking, resistance, sisterhood, and feminist activism, culminating in the creation of a menu/manifesto on feminism and cooking. The scenario takes place on the last eve before the fall of patriarchy. Feminist activist groups across the globe are meeting in preparation. One of them is the feminist-terror cell Ultra Violet, whose expertise lies in nutrition, cooking, and the transformative power of food. During their final gathering, they focus on preparing a meal that not only fuels their strength for revolution but also nourishes their vision for a post-patriarchal world. In Ultra Violet, players take on the roles of activists. Each character is associated with an ingredient, which serves as the basis for character creation. During the preparatory workshop, players craft characters based on ingredients, collectively establish a group identity, and write invitation letters to the last supper before the fall of patriarchy.

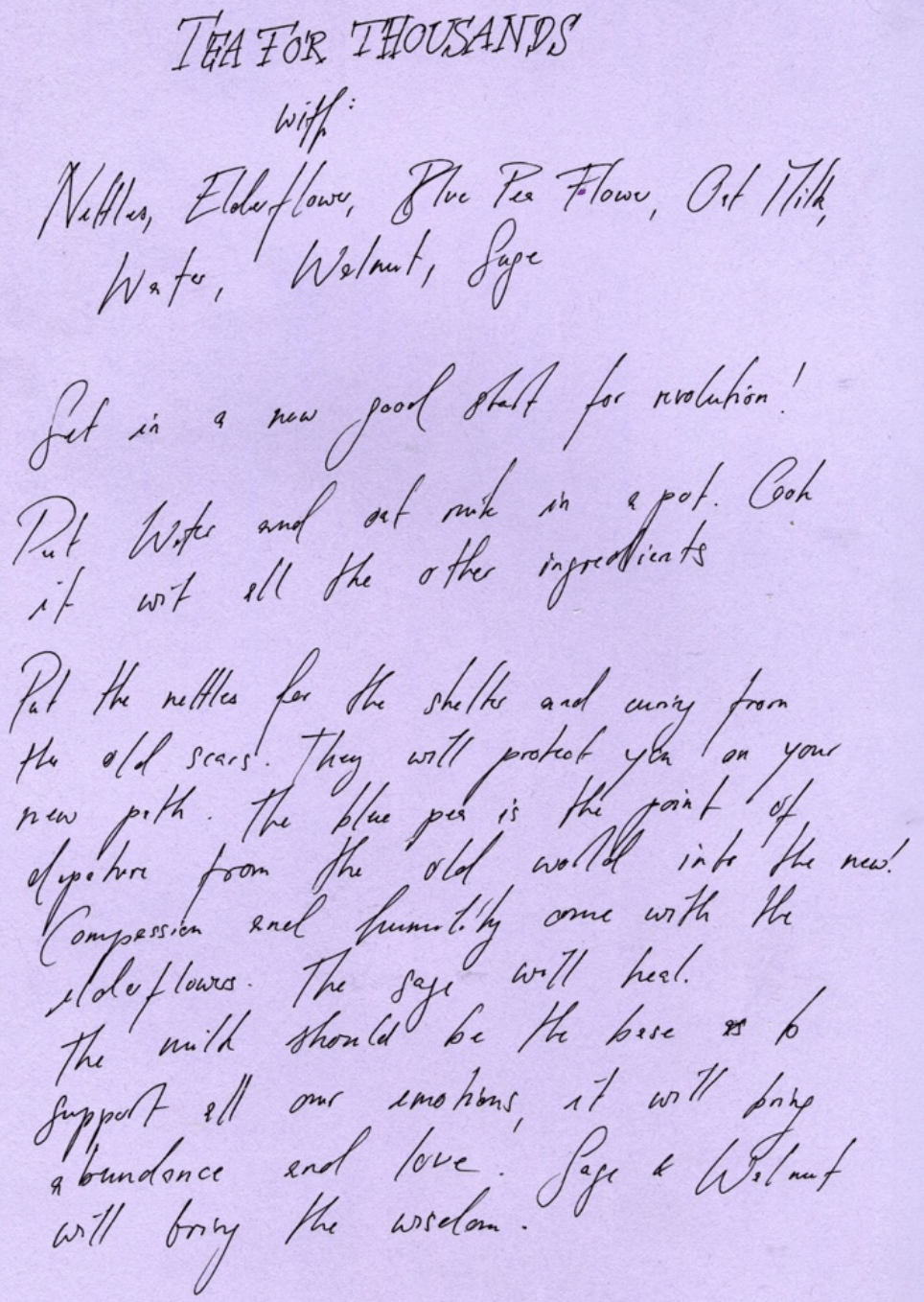

The supper consists of four courses consisting of drinks, salad, bread (tartines), and dessert. Each course is prepared by a smaller group of 2-3 players and focuses on a thematic aspect related to revolution and feminist world-building: reason & idea, strength & power, feelings, and dreams & hopes. The game begins with each player reading an invitation to the last supper written by another player. The letters, written in the beginning, function like self-fulfilling prophecies by the players. Following a group greeting, they divide into smaller groups, each tasked with preparing one of the four courses. Players have 40 minutes to create a course using the ingredients brought by their characters and reflecting on the assigned thematic aspect. They are also prompted to document their recipe and provide notes and thoughts related to their theme. In the second part of the game, players reconvene for the last supper. Each group introduces their dish, recipe, and reflections to the whole group. While the group enjoys the meal, others can contribute additional thoughts and reflections to conclude this part of the menu/manifesto. The creation of the recipe was simultaneously the creation of manifestos and players would engage in the activities of cooking and manifesto writing.

The great thing about playing is that you don’t have to know how to do a certain action in order to play it, you just have to pretend as if. In Ultra Violet, players did not need to know the efficacy of each ingredient in order to create a recipe with a specific effect. But they could experience being in the position of experts, knowing how to create potions, confident in being strong enough for the upcoming struggle. One conclusion that could be made about the knowledge produced in this game is that the players gained the knowledge about how to create and prepare a recipe. Inside the game the recipes were to be created with a specific purpose. They had to provide nourishment to feminist activist groups in preparation for a post-patriarchal world. In order to create a recipe that has a certain effect, one has to know different active ingredients and combine them in such a way that they achieve the desired effect. In the specific case of Ultra Violet, players also had to know the need for an effect in order to create a recipe for it. The knowledge about the efficacy of each ingredient was provided to the characters, in that way players did not have to have any prior knowledge about it. Moreover the efficacy of each ingredient was partly fictional, based on symbolic attributes rather than chemical. This means while characters inside of the LARP had knowledge about what each ingredient can be used for, players did not bring this knowledge to the game and would also not leave the game with such a knowledge.

Menu/Manifesto created inside the LARP Ultra Violet, May 2024

But not everything in the game was pretend play, because in the end the players actually wrote recipes and manifestos and the execution of these actions also produced a certain form of experience. In their essay “‘Gods in World of Warcraft Exist’: Religious Reflexivity and the Quest for Meaning in Online Computer Games.” Sociologists Schaap and Aupers conclude that the pretending of an activity inside of a game creates a space to reflect on that activity.[10] In that sense creating a recipe and manifesto for a feminist revolution encourages players to reflect upon (feminist) activism. It can therefore be concluded that in the LARP Ultra Violet, by taking on roles that will undoubtedly see the end of patriarchy, knowledge was gathered about what life after patriarchy would look like. At the same time, the game also became a place to reflect on feminist activism and how it can be nurtured as players cared for each other, dined and wrote menus/manifestos.magic beyond the circle

As a LARP creator in the context of the art world, I often wonder how, and if, the knowledge created within a LARP, through the experiences of individual players, can be beneficial to the world outside the game. Can there be a second, delayed audience that benefits from it? Reasons for this include that a LARP is not always accessible to everyone- it might be geographically or temporally out of reach, or player capacities might be limited. Another reason, especially in the art world, is that LARP is a very demanding medium, and many people are hesitant to participate. Furthermore, a LARP can require many resources, which are difficult to justify to funding bodies if the audience is small due to player capacity. However, documenting a LARP is a major challenge, and it is sometimes questioned whether it is even feasible or meaningful to serve a delayed audience with it because technically, a LARP only exists in the moment of the play, when players draw and maintain the magic circle together by playing out their roles.

In their essay The Making of Nordic LARP: Documenting a Tradition of Ephemeral Co-Creative Play, LARP scholars Jaako Stenros and Markus Montola reflect on the aesthetic of LARP, which is an aesthetic of doing. The authors identify five attributes that make LARPs so difficult to document, in that they are subjective, co-creative, aimed at a first-person audience, ephemeral, and have a loosely defined purpose. But it is also these attributes that make LARP so specific in the experience it offers as a medium, and the question still arises- to what extent is it even possible or sensible to want to reproduce experience through documentation?

The typical way LARPs, and events of similar nature such as performances, workshops or social events, are documented are photographs of the happening or individual reports. Photographs often show a group of people doing something, depending on the LARP they are dressed in perhaps with theatrical lighting. These images serve as proof that the LARP has taken place and may also have an emotional value for participants. However, they are neither informative about the experience of playing this LARP nor about what form of knowledge is jointly generated. The individual report, if written, can give more information about the experience of an individual player in a LARP. The play scholar James Hans suggests that play is only separated into a sensuous and a rational experience after the play.[11] Therefore, the re-telling of a LARP experience is beneficial for the player as it provides them with a space for reflection and creation of meaning. However, the re-told narrative is incomplete as it is only a single, fractional perspective on the LARP and can’t provide a delayed audience with a full picture. Documenting a LARP means attempting to capture the fleeting, embodied, and often intimate experiences that occur within the game. This can include video recordings, photographs, written accounts, and interviews with players. These forms of documentation can never fully capture the richness of the lived experience within the game. They can, however, provide glimpses and reflections that offer some insight into the experience for those who were not present. This material can also serve as a way to reflect on and analyze the game itself, providing valuable feedback for future design and understanding of the medium. It creates a record that can be shared, discussed, and learned from, contributing to a broader discourse around LARP and its potential as a tool for knowledge production.

As a LARP designer I have been trying to incorporate documentation as part of the play. In my first attempt it was incorporating other media deeply into the design such as making a game played in a video conference or an online radio stream or making one character a camera-journalist. Even though another storytelling medium was deeply integrated into the design of the LARP, it does not change the fact that the documentation does not reflect the sum of subjective embodied experiences that collectively create the experience of playing that LARP. Nevertheless, they can reflect a mood and give an insight into how spontaneously and collectively stories are created inside of a LARP setting and what visions and knowledge might be generated by the players.

The following audio sample was created inside Eixogen, a LARP thematising smart-city technology which took place in Rotterdam in 2023. It was commissioned by and designed in collaboration with the artist Louisa Teichmann, who researches the implications of smart city technology on our communication, movement and personal freedom in urban life in the face of Rotterdam developing into a smart city by 2025. The goal was to make players imagine what life in a smart city could look like and by doing that, play out the effects it would have on everyday life. Furthermore the game aimed to find ways to counter or challenge smart city technology and its effects on everyday life. Players were playing a group of rebels who were running the self-organized underground online radio station 868mHz. Their broadcasting activity emerged as a response to the pressing issues arising from the rapid transformation of urban space in which every area of citizens' personal life has become commodified and monitored. In a world where human experience gets reduced to mere data, numbers, consumer behaviorism and government surveillance is accepted without resistance. The members of 868mHz share feelings of alienation and powerlessness and are driven by a need and desire to create a platform for expression, connection, and dialogue amidst the challenges and changes within their everyday life in the smart city.

Originally, we were speculating that all the radio-shows created in the LARP would offer great material to create a radio drama which would on the one hand retell the story of the LARP and on the other hand present the knowledge generated by the players in the form of future imaginations of what life in a smart-city of the future could look like. These ideas could also help people outside the game to imagine life in the future and reflect on what is desirable and what is not. However, I had to admit to myself after listening to the material that even though the game was exciting, the retelling of the story doesn't make for a particularly exciting narrative. And even though there are many interesting ideas in between, they are difficult to understand without context. They are similar to retellings of a dream, exciting for the dreamer to tell but difficult to listen to because they have no clear story arc or punch-line. To go back to the image of the Oracle, They are cryptic messages from another world, except that they are put out into the world without question and thus provide no incentive to decipher them.

The author and Associate Professor in Art Education Jason Cox discusses in his article Documenting LARP as an Experience the challenges and problematics of documenting a LARP. He suggests that player-created artifacts can serve as meaningful documentation, capturing the essence of the experience rather than a linear narrative. This approach aligns with the idea that meaning is derived from lived experiences and personal interpretations rather than objective accounts. Cox argues for the value of "participant-made art as data"[12], which allows for subjective experiences to be presented and understood through individual narratives and emergent patterns. These artifacts could potentially become social objects that describe experiences from multiple perspectives, as he says “souvenirs from alternate realities” encouraging engagement and deeper understanding of what players might have experienced during the LARP. In the case of Ultra Violet, Lucila has cooked one of the recipes to a delayed audience and re-told the story of the LARP while serving the warm and sweet “tea of the thousands”. Even if this tea does not have the superpowers that the players may have experienced through it in the game, reading the recipe and tasting the result together with the retold experience is a multisensory experience in itself that provides a broader spectrum for reflection on the experience of the LARP than, for example, my sentence example no. 3 at the beginning of this essay:

I spent the last night before the fall of patriarchy with my sisters. While we drank the tea of thousands, we realized how silent the world would become.

The documentation of LARP experiences, though complex, can offer insights into a player’s experience and help a delayed audience relate to it.

In conclusion, I argue that LARPing can be a tool for knowledge production. Rather than producing factual knowledge, it generates an awareness of the possibility and plurality of knowledge. In a way, it enables us to become oracles, speaking out messages that could become wisdom depending on how we read them, and prophecies that could become reality depending on how we act upon them. LARPing makes one look beyond one's own scope and creates awareness of the limitations of one's own knowledge and experience. By immersing into different roles and scenarios, it fosters empathy, broadens perspectives, and challenges traditional notions of knowledge and truth. What we gain from LARP are not concrete answers but approaches to further our own knowledge, broaden our perspectives, and prophecies of alternative realities. However, the challenges of accessibility and documentation mean that the benefits of LARPing are not always easily shared with a wider audience. Even though the experience of participating might not be feasible to reproduce for a delayed audience, it is possible to create artifacts that can act like messages or prophecies for alternative realities.

Bibliography

- Alder, Avery. The Quiet Year. Buried Without Ceremony, 2013. Accessed July 30, 2024. https://buriedwithoutceremony.com/the-quiet-year .

- Boal, Augusto. Games for Actors and Non-Actors. 2nd ed. Translated by Adrian Jackson. London: Routledge, 2022. Cox, Jason. "Documenting Larp as an Art of Experience." International Journal of Role-Playing 9 (2018).

- Hale, John R., Jelle Zeilinga De Boer, Jeffrey P. Chanton, and Henry A. Spiller. "Questioning the Delphic Oracle: When Science Meets Religion at This Ancient Greek Site, the Two Turn Out to Be on Better Terms than Scholars Had Originally Thought." Scientific American (August 2003): 66-73.

- Hans, James S. The Play of the World. Amherst, MA: The University of Massachusetts Press, 1981.

- Huizinga, Johan. Playing and Knowing: A Study of the Play-Element in Culture. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1949. Koljonen, Johanna, Jaakko Stenros, Anne Serup Grove, Aina D. Skjønsfjell, and Elin Nilsen, eds. Larp Design: Creating Role Play Experiences. Denmark, 2019.

- Leavy, Patricia. Method Meets Art: Arts-Based Research Practice. New York: The Guilford Press, 2015.

- Montola, Markus, and Jaakko Stenros, eds. Nordic Larp. Stockholm: Fëa Livia, 2010.

- Montola, Markus, and Jaakko Stenros, eds. "The Making of Nordic Larp: Documenting a Tradition of Ephemeral Co-Creative Play." In Proceedings of DiGRA 2011 Conference: Think Design Play. DiGRA, 2011.

- Salen, Katie, and Eric Zimmerman. The Rules of Play: Game Design Fundamentals. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2004. Sandberg, Christoper. "Genesi. Larp Art, Basic Theories." In Beyond Role and Play: Tools, Toys and Theory for Harnessing the Imagination, edited by Markus Montola and Jaakko Stenros. Ropecon, 2004.

- Schaap, Julian, and Stef Aupers. "'Gods in World of Warcraft Exist': Religious Reflexivity and the Quest for Meaning in Online Computer Games." New Media & Society, 2016. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444816642421 . Zagal, José P., and Sebastian Deterding, eds. Role-Playing Game Studies: Transmedia Foundations. New York: Routledge, 2018.

- "Why Did the Oracle of Delphi Call Socrates the Wisest Man?" The Collector. Accessed July 30, 2024. https://www.thecollector.com/why-did-the-oracle-of-delphi-call-socrates-wisest-man/ .

Artist Bio

Sophie Allerding (she/they) is an interdisciplinary artist interested in the ways we tell stories to each other and how they shape the world around us. Rooted in worldbuilding and speculative fiction, Sophie’s practice spans visual and social art, crafting alternative realities and exploring collaborative storytelling to challenge dominant narratives, such as human dominance, over the natural world gender-based power imbalances and the hegemony of Western knowledge systems. Their work offers a platform for re-imagining these narratives and empowering individuals to reshape them.

Sophie is an active member of the feminist collectives POSSY and Radio Echo Collective and is part of .zip, an artist-run interdisciplinary project space in Rotterdam.

Sophie’s work was presented among other sites in the Deichtorhallen Museum for Photography (DE), Landesmuseum Koblenz (DE) Hallo: Radiofestival X-Kanal (DE), the Climate Utopias Festival (FI), Goethe Institut Vietnam (VNM) and Climate Art Fest (DE) and Centro del Imagen (MX), Staatliche Galerie Karlsruhe (DE) and Het Nieuwe Instituut, Rotterdam (NL).

2. This reflection is based on my experience as a player in the game Spillover, designed by Alex Brown, played at the Black Box Festival, Copenhagen, 2023.

3. This reflection is based on my experience as a player of the game Ultra Violet designed by me in collaboration with Lucila Pacheco Dehne, May 2024.

4. Hale, John R., Jelle Zeilinga De Boer, Jeffrey P. Chanton and Henry A. Spiller.“Questioning the Delphic Oracle: When science meets religion at this ancient Greek site, the two turn out to be on better terms than scholars had originally thought.” Scientific American (August, 2003): 66-73.

5. Sandberg, Christopher. (2004): “Genesi. Larp Art, Basic Theories''. In Montola, M. & Stenros, J. (eds): Beyond Role and Play. Tools, Toys and Theory for Harnessing the Imagination. Ropecon. P 274-277

6. The term Magic circle was originally coined by Johan Huizinga.

7. Salen, Zimermann, Rules of Play: Game Design Fundamentals. Cambridge, MA:MIT Press., p.95

8. Erik Fatland 2014, emphasis added, roleplay studies, page 234

9. Huizinga, homo ludens, p. 113

10. Schaap, Julian, and Stef Aupers. 2016. “‘Gods in World of Warcraft Exist’: Religious Reflexivity and the Quest for Meaning in Online Computer Games.” New Media & Society. doi:10.1177/1461444816642421.

11. As cited in Cox (2018) James Hand, The Play of the World (1998)

12. As cited in Cox (2018) Leavy, Patricia. 2015. Method Meets Art: Arts-based Research Practice. New York: The Guilford Press.

Politics of Knowledge (2022–24), Lectorate Art Theory & Practice at the Royal Academy of Arts.